From Nam June Paik to Jenny Holzer, artists have playfully engaged with technology to create new forms of art such as Net, Software and Digital art. Not only have these artists been able to produce new forms, but have transformed traditional practices of painting, drawing, and sculpture by using digital techniques and media. Artists currently create artwork using networks, artificial intelligence, virtual reality, in video games, on the internet and even on our own mobile devices. This past fall, Jenny Holzer used Augmented Reality (AR) to create the exhibition You Be My Ally which had a wide-reaching impact as a form of public art during Covid-19. Exciting as these new art forms are, how do we accurately capture and preserve them? What role should thinking about conservation play in both curating and the artists’ process? These are the questions that greet professionals working with digital and time-based media artworks.

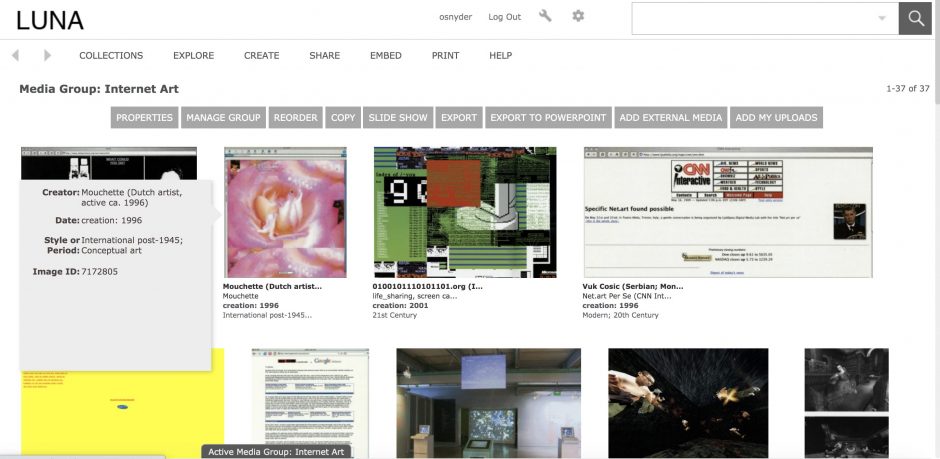

As hardware and software become more refined throughout the 20th and 21st century, many digital and time-based media artworks, such as Nam June Paik’s, have presented challenges to conservators of collections. Traditionally, conservation has focused on fine-art conservation with an effort to minimize loss or damage to the artwork’s authentic material elements. In this practice, artwork has been defined and identified by the materials. However, digital and time-based media artworks are vulnerable to change because of the limited availability of technology for which they were originally made. A clear example of this exists in the digitization of video artworks on VHS. This form of time-based media is dependent on technologies that are now obsolete exposing the artwork to change in order to preserve it— a fundamentally different ideological approach to traditional conservation because the artwork is now separated from its authentic material elements. As a result, digital and time-based media artworks require an expansion of traditional conservation efforts and consideration within collections.

Preserving digital and time-based media artworks is an ongoing and collective practice. It requires collaborating closely with curators, conservators, and installers work closely and consult regularly with artists or their estates, studio, or galleries. Caring for digital files is not completely different from caring for art objects in other media, but because time-based and digital media require a proactive approach to care and management, this project is critical in gathering information that will ensure their display and care into the future.

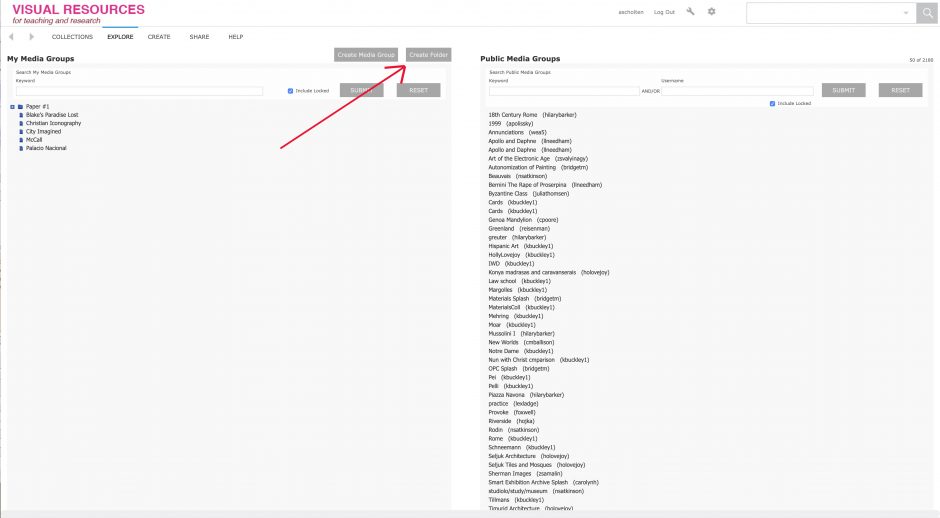

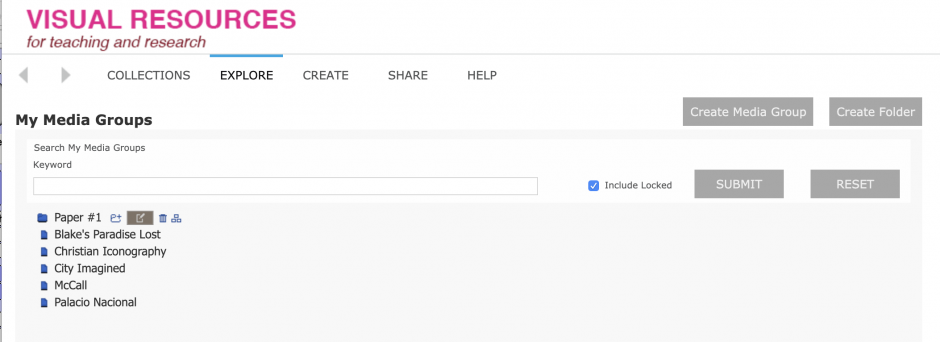

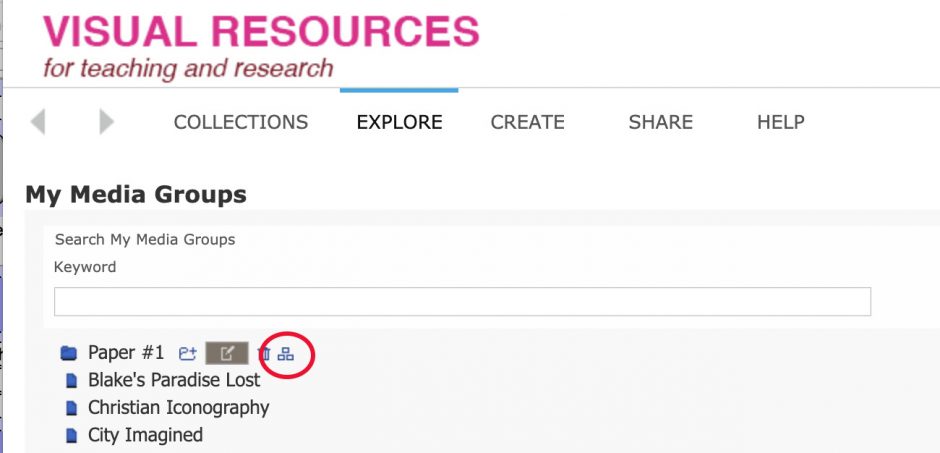

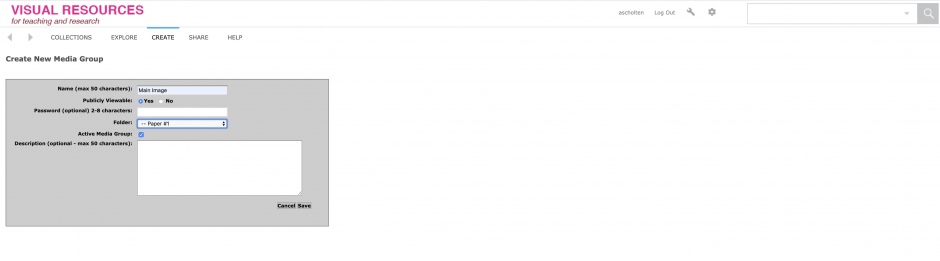

We must continuously revisit and consider the framework of how digital and time-based artworks may be preserved in our current collection. In addition, we must attend to the conservation of the reproductions of digital and time-based art. Part of the efforts currently being made by the Visual Resource Center (VRC) is to emphasize the importance of documentation — a work’s physical remnant or trace. This project is being completed by identifying and analyzing a number of problems and/or practices, from an institutional, artistic and researchers’ perspectives about digital and time-based media’s documentation. Then, applying this knowledge to the VRC’s own practice and catalogue in the Art History Department Image Collection.

The following interviews aim to share experiences as well as discuss strategies for the documentation, conservation, and preservation of digital and time-based artworks for and by artists, curators, and conservators. To jump directly to a specific interview within this essay, click on the name of the interviewee below:

Jenna Post

Jenna Post is an Assistant Registrar at the Smart Museum of Art.

You have worked as a registrar at the Smart Museum for several years gaining experience cataloging a variety of media, how do you approach the challenge of conserving digital and time-based media?

As a registrar, my primary concern is about the care and documentation of the works in the Smart’s collection, so my approach is centered around determining the information we need to document for each work in order to manage it. Of the approximately 16,000 works in the collection, there are nine that include a time-based element such as an audio recording or video. Because this is a small subset of the larger collection, I’m able to assess each time-based work individually.

When we catalog an installation work at the Smart, we create a primary record for the artwork, as well as secondary records for its “related accessories”. This helps to track components that are not necessarily a part of the artwork themselves, but which are necessary for the display or storage of the work. For example, a related accessory for an installation artwork (not time-based) might include a specially designed storage crate or display stand. For a time-based artwork, such as Tempelhof Tks 5 & 7 by Eve Sussman & The Rufus Corporation, which is a 2-channel video installation, the related accessory records include DVD players, various electronic components, and an exhibition copy DVD disc for each video channel. The documentation and tracking of these “accessories” are crucial to the care and conservation of time-based works, because this helps to assess whether the components will require conservation or replacement, and what the needs might be.

For managing digital files, I perform regular audits of our collection-related digital records to check file integrity. This includes our files stored on discs and hard drives as well as files stored in the cloud. Our database also generates checksums for files when they are added to the system which helps to monitor for any changes or errors.

What limitations are you currently facing in cataloging digital and time-based media?

Within the next year, we’re anticipating the need to increase the cloud storage capacity of our digital repository with additional dedicated space for time-based media artworks, as we are looking to acquire master digital files for works in the collection which have files currently stored on DVD discs and hard drives. Best practices evolve as new technologies become available and more accessible, so we want to make sure that we have the highest quality versions of a file possible, stored using the ideal methods.

This has also come up concerning our time-based media content related to the Museum’s activities, such as artist interview videos and virtual exhibition tours. Although our holdings of time-based media artworks remain relatively small, the amount of digital time-based content produced has grown dramatically, especially during 2020 when the pandemic made us all shift to the virtual sphere.

What resources have had the most impact on your process when cataloging digital and time-based media?

The Matters in Media Art project has been an especially good resource for the Smart’s collections team in thinking through the steps and processes involved in acquiring, cataloging, and preserving a time-based media artwork. It’s provided some much-needed clarity for us about the questions we need to ask when acquiring an artwork to steward it in the best possible way.

What are some of the considerations you make when preserving artwork in the Smart Museum’s collection?

One of the major considerations is how to balance preservation needs with access to artworks in the collection. For traditional collection objects, such as a woodblock print with ink on paper, the preservation requirements will reflect the object’s sensitivity to light, humidity, and handling. For a time-based artwork or digital file, its associated physical components or accessories may need similar considerations, but the digital component adds another layer of complexity to this.

As a University museum, the Smart’s collection is used in teaching, so it is essential to be able to share images of artworks with faculty and students. For time-based and digital art, however, this poses some new questions, for example, about the variability of certain installations, whether we could share a portion of a larger video work in a lower resolution but more accessible format, or screen a video from a larger installation separately from its other components. It’s essential to have specifications for access (sub-master) copies for these types of works, as well as clarity about how they can be used by the Museum.

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy

Zsofi Valyi-Nagy is currently a PhD candidate in modern and contemporary art history at the University of Chicago.

Your current research combines archives, interviews, and object-based study about a pioneer of computer art, Vera Molnar. What challenges have you encountered when coming across documentation and preservation of artworks from decades ago?

This is a great question. I think it’s important to recognize that documentation can be hugely subjective. What I mean is that, especially with early work, the artwork that remains preserved and/or documented is largely a result of the artist’s own decisions of what work matters to them. I have had some conversations with Molnar in which she expressed regrets about what she chose to keep or throw away. For example, she regrets throwing away her “failed” computer drawings from the late 1960s and early 70s––those that, due to a typo in the code, didn’t turn out the way she had wanted them to. She also didn’t keep any record of her programs from this period, which has posed an interesting challenge in understanding the relationship between her code and her images. There’s actually a community of programmers on Twitter who have reverse-engineered Molnar’s computer drawings and re-programmed them in Processing or other twenty-first-century programs. This kind of contemporary practice is extremely helpful to researchers like me, who are less skilled in programming.

What forms of documentation have had the most impact on your research?

Embarking on a monographic research project focused on one artist whose career spans 7+ decades can be overwhelming, but I’m very fortunate in that a huge bulk of Molnar’s work was already documented, mostly in the early 2000s, by a French art historian named Vincent Baby who worked closely with Molnar to create a catalogue raisonné website as a part of his own doctoral research. Vincent’s groundwork has been an invaluable resource to me. Unfortunately, the obsolescence of Flash Player in late 2020 means that Molnar’s website is currently down until the images can be transferred to a new platform, but luckily my dissertation adviser Christine Mehring had the brilliant foresight to advise me to download all the images before this happened. With the guidance of Bridget Madden, I catalogued them all in Tropy, along with other documentation I’ve done myself. This has been a godsend for my dissertation—I can just search for a keyword like “Love Stories” and see all the work Molnar has made over the course of her career around this theme.

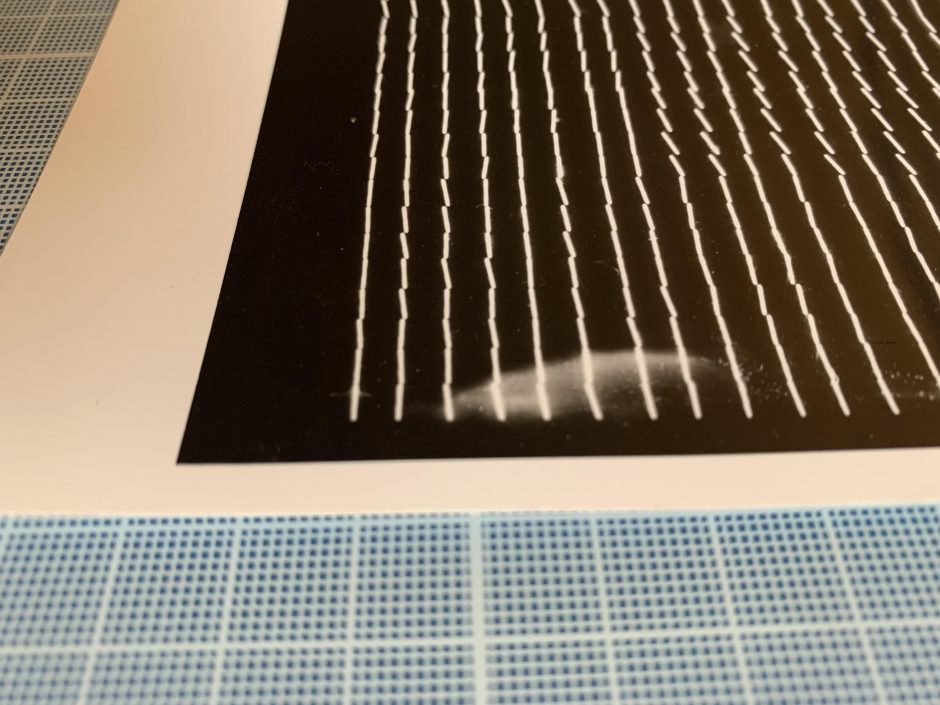

Since fall 2020, I’ve been really fortunate to have been based in Paris as a Dedalus and Fulbright fellow, and so my fieldwork has been focused on documentation of artworks remaining at Molnar’s home/studio as well as the documents in her archive, which are organized thematically rather than chronologically (this, too, has given me insight into how Molnar conceptualizes her own practice). I’m the sort of art historian that is interested in the “stuff around art” perhaps even more than the art itself—we had a stimulating conversation about this with Jenn Sichel and Matthew Jesse Jackson at the workshop I co-coordinate, Speaking of Art: Artist Interviews in Scholarship and Practice, earlier this year. That is to say, the most impactful objects for me have been undocumented photographs, notes, and manuscripts in the Molnar archive. I have a whole dissertation chapter about what I call Molnar’s “screenshots,” these black-and-white photographs she took in the 1970s to document the earliest computer screens, which were CRT vector displays. She didn’t necessarily intend these to be artworks in themselves, and that ambiguity has been a really generative starting point for me. You might say I’ve spent a lot of this year documenting documentation and thinking about how documentation factors into the artistic process.

What limitations are you currently facing in your research based on issues surrounding documentation and preservation of the artworks?

Working with the archive of a living artist is tremendously exciting, but it comes with its own set of challenges. I hope to eventually turn my dissertation into a book with nice images, but it has been tricky determining how to secure my rights to reproduce these materials and to maintain those rights once the artist has passed on. The VRC has been super helpful with pointing me to copyright resources, but I’m still in the middle of figuring out the best practices for publishing around a transnational project that will draw on material from many different jurisdictions.

In addition, working with a non-institutional archive and collection means that I have to be more creative with documentation since, there aren’t already imaging resources in place. For example, Molnar doesn’t have a high-quality scanner in her studio. Luckily, with some studio funds, we were able to purchase a scanner that the VRC recommended (the Epson V600), which I’ve been using to digitize many photos and slides from her archive. The scanner is fantastic, but it’s not large enough to document many artworks, so I’m still waiting to hear back about an equipment grant to purchase a camera, since I’m too far away from campus to loan from the VRC. That said, some artworks, like her 10-foot long computer plotter drawings on roll paper, are going to be difficult to document using traditional methods; for these, I would love to invoke some of the methods used by https://scrolls.uchicago.edu/.

Can you discuss what documentation means and how it influences the value and experience of the “original” artwork?

In terms of value, I think that having good images to support your writing is extremely valuable not only for research but also for things like grant and fellowship applications. Most of the work I’m writing about either hasn’t been documented before or if it has been documented, the image quality isn’t up to par with current printing and publishing standards. The better documented it is, the more these images can circulate and the more widely the artist’s work will be known and recognized.

In terms of how documentation influences experience, one thing that has been huge for my research is being able to virtually reunite Molnar’s serial works that have been separated through the process of acquisitions and sales of individual drawings or partial series. The cool thing about Molnar’s early computer drawings is that there’s a time stamp on them that shows you when each drawing was calculated, down to the millisecond. Tropy has been hugely helpful here, because it allows me to sort images by their time of creation. I can see which different series Molnar was working on simultaneously, and I can compare their order of making to the chronology Molnar sometimes retroactively imposed on the work. In addition, having digital copies of a series allows you to have a different viewing experience. Rather than physically moving your body to watch a series progress from one sheet of paper to another, you can toggle through a series of images and watch the composition transform in the space of the screen, which in some ways is more faithful to the way Molnar would have originally experienced it. Having this insight, combined with the “reverse engineering” of code that I mentioned above, has really transformed the way I look at these works on paper.

If I understand correctly, you are also an artist yourself. Could you share a little bit about your practice? What kind of considerations do you make when documenting your artworks?

I am! Thanks for asking about my practice. I work in a variety of mediums, but since the beginning of the pandemic, I’ve mostly made “offline” two-dimensional work: collages using inkjet or laserjet prints of photos I’ve taken with my phone, painted over with gouache and gesso. My quarantine “paintings” each explore a different room in my own home, this sense of claustrophobia we’ve all felt from being confined inside combined with the tenderness and care that goes into nesting. These works have been relatively easy to document, but my past work with more experimental media have posed more challenges.

For example, I’ve made analog holograms in a proper holography lab as well as with “instant” holography film in my own home, and these are notoriously difficult to document. Materially speaking, they are two-dimensional objects, but the image is three-dimensional with a sculptural quality. I collaborated with the brilliant Pengxiao Hao from Northwestern University’s Center for Scientific Studies in the Arts, who has developed a technique for documenting holograms in gif form; she made a fantastic gif of one of my holograms that captures the iridescence of the object, how it changes color as you view it from different angles (viewable on my website, https://www.zs-vn.com/artwork). From 2014 to 2016 I made a body of work using the 3D scanning app 123DCatch, which is now obsolete. With that work I faced a lot of challenges with cross-application and cross-platform compatibility of file formats. What I have left of the work are mostly screenshots and screen recordings I made years ago. I wish I’d made more considerations concerning the longevity of the work, but at the same time part of my interest in working with these sorts of technologies lies in their shortcomings—their inability to capture certain kinds of surfaces or environments.

Livy Snyder

Livy Snyder is a graduate student at the University of Chicago working at the Visual Resource Center as a Metadata Research Associate.

As a metadata research associate at the VRC, you work in depth with questions about documentation. Can you share more about your specific research in documentation of digital and time based-media?

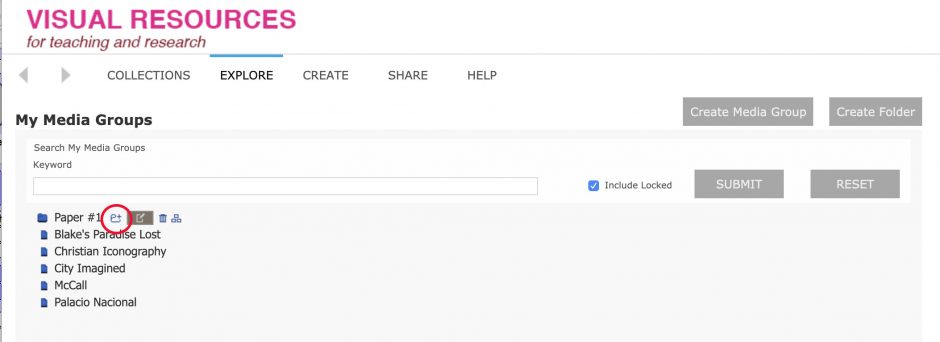

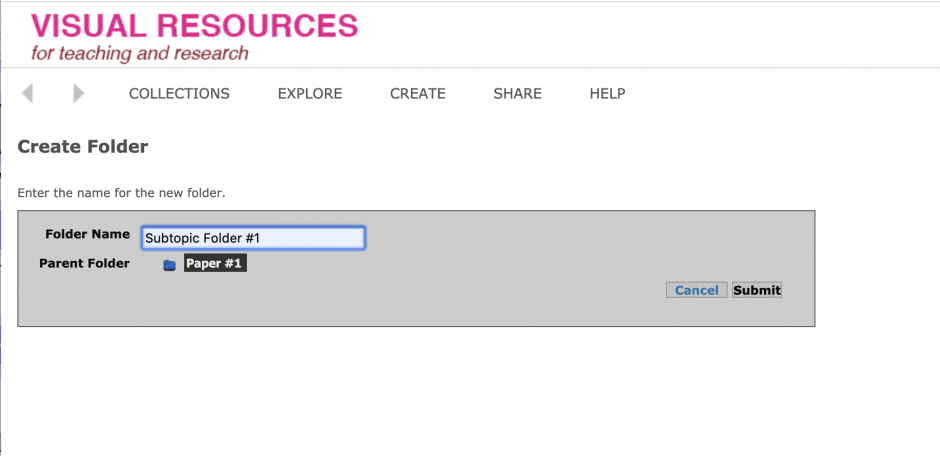

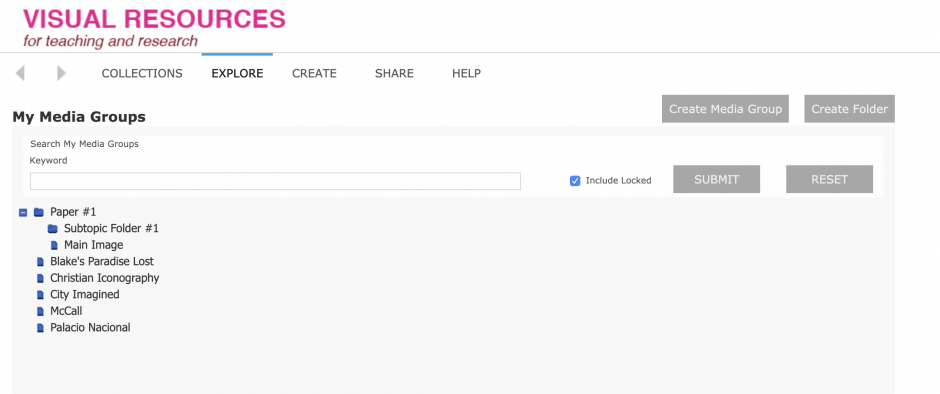

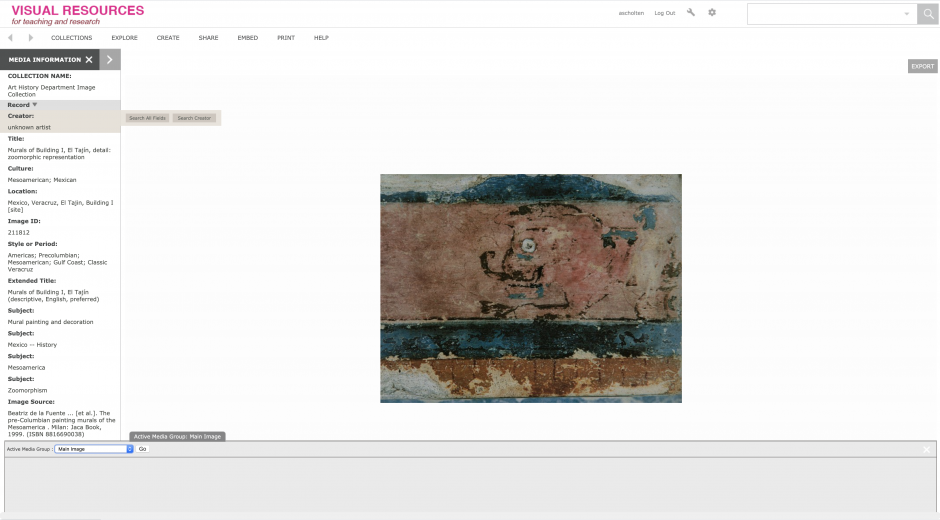

In my role at the VRC, I am completing a Critical Cataloging project to repair digital and TBMA records in the collection. The goal is to assess library metadata, cataloging, and classification standards, practice, and infrastructure. This requires ensuring a framework and resources for future and existing records by working with a cohort. I have conducted research on digital and TBMA records based on the process of gathering details about the artwork, its installation process, and the artist’s intent. I also consult the Getty’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus standards and museum initiatives like Guggenheim Variable Media Initiative as well as organizations such as Matters in Media Art, DOCAM Research Alliance, and Lab for Unstable Media to name just a few.

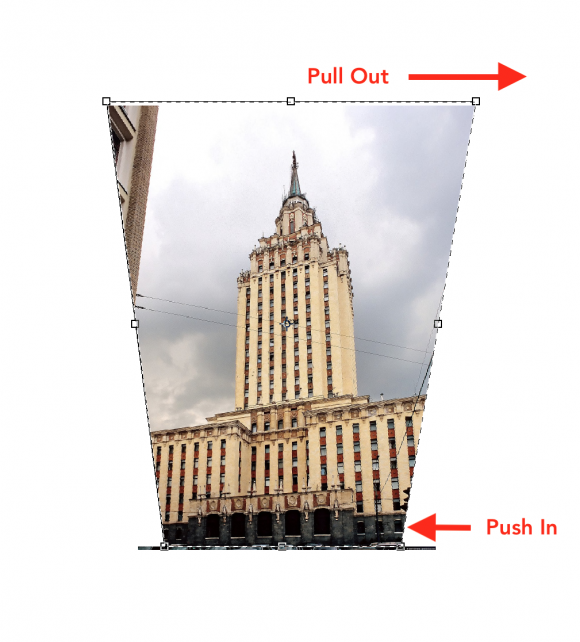

What does repairing a file’s record look like? Can you describe the process?

Each metadata record is addressed individually in the collections management system, LUNA. It’s very important to take a holistic approach when repairing records by considering all aspects of the record as much as possible. When an artwork has many details that one might want to document, the question becomes— what are the most important aspects about this piece and what will be helpful to researchers to include in the work’s record? In other situations which are more common, there exists very little information which requires some heavy research. Most frequently in my project, I have added a description to record the specific materials which are not always listed in classification standards. The description also helps to illustrate how the various components of the piece work together and clarify the artist’s intent and meaning behind the work. Many of the subject headings, techniques, titles, can mislead the researcher because they are so distanced from the work itself based on a lack of infrastructure for digital and TBM artworks. Working closely with records in this way really shows that there is a politics of archives, technologies and discourses that needs to be uncovered not only because of what the types of media being documented but how it’s documented and for who. I have found that caring for digital and TBMA files is a great way to think about how the cataloging framework can grow to become more inclusive because it inspires new ways of thinking about documentation practices.

What resources have had the most impact on your project?

While I think that there are so many resources that have helped me in my project — including the resource of my supervisors and cohort who are available to help guide me in repairing records— there are a few scholars and an artist that I continue to reference because of the insightful questions they pose in their own research projects about documentation and collection of digital and TBMA. I recently had the opportunity to attend a conference through LIMA which is a platform for media art based in Amsterdam that promotes critical understanding of media art and technology and sustainable access to media art. Their work includes researching preservation, research and distribution of media art. I gained a lot of knowledge about the field from the conference including the work of Annet Dekker who is an Assistant Professor Media Studies: Archival and Information Studies at the University of Amsterdam in the Netherlands. I have already bought two of her books and use her website quite often. I also appreciate the work of Ofri Caani who is an artist focusing on ruins of the web and provides a great model for thinking about incorporating audience-based documentation. One of her recent projects is based on the questions: “what happens when a museum is dissolved? What happens if the museum dissolves and doesn’t have an online collection?” As an artist, she is in a position to experiment and challenge ideas of the collection and documentation standards which makes her work really valuable.

– Livy Snyder MAPH 21′