by Michaela Appeltova

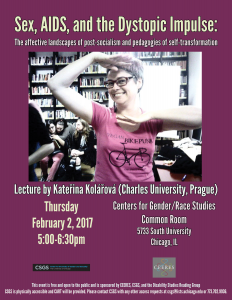

On February 2, Kateřina Kolářová, Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies in the

On February 2, Kateřina Kolářová, Assistant Professor of Cultural Studies in the

Department of Gender Studies at Charles University in Prague, presented a theoretically dense, analytically layered, and thought-provoking excerpt from her manuscript on the intersections of disability, race, sexuality, and post-socialism in the Czech Republic. The event was sponsored by the Disability Studies Reading Group, Center for East European and Russian/Eurasian Studies, and Center for the Study of Gender and Sexuality.

Czechoslovakia (later the Czech Republic) was long considered the model country of the post-socialist transition, but like most other East European countries it did not escape a period of affective disillusionment after the fall of communism in November 1989. In 1997, public opinion polls noted that more than half of the population thought that their “post-November dreams are not being fulfilled.”[1] Václav Havel’s speech in the Parliament that same year identified the discontent of Czechs with the political system and the pervasiveness of a “bad mood.” Popular opinion had shifted from optimism and faith in the capitalist future towards what Kateřina Kolářová calls dystopic disaffection.

The main thrust of the talk was Kolářová’s analysis of how this disaffection is portrayed in three films by the Polish émigré film director Wiktor Grodecki. Depicting male sex workers in Prague, and allegedly based on their true stories, the films garnered a lot of public attention. Often darkly shot and accompanied by a gloomy score, the films portray Prague as a dystopic cityscape, a “Sin City of the East” as Kolářová put it, filled with gambling stations and casinos, drug abuse, rampant street prostitution, and death from AIDS. She showed a few clips from the last film in the triptych, Mandragora (1997), a tragic Bildungsroman narrative about the coming of age of the young hero Marek, prostituting himself in order to pay for drugs, which Kolářová read as an allegory of the coming of age of the young nation. Symbolizing the nation’s collapsing moral order, Marek dies of a deliberate overdose in a public bathroom.

Mobilizing a variety of theoretical insights and scholarly analyses – Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick‘s “homosexual panic”, Susan Gal and Gail Kligman’s gender analyses of post socialism, Roderick Ferguson’s rereading Marx’s notion of alienation as feminization, Lauren Berlant’s “live sex acts,” Matti Bunzl’s “imperialist economics” of cross border sexual encounters, and Chaundran Reddy’s challenge to queer theory to thoroughly engage with race – the talk provided a breathtakingly nuanced analysis of the movies’ context. Specifically, Kolářová focused on the ways in which they validated what she called “capitalist rehabilitation,” a disability/crip narrative of restorative politics.

A central motive of the movie is a critique of commodity capitalism, and the (perverse) consumption of goods, bodies, sex. Or more precisely, it presents a critique of “quick money” and Western consumption that, as the film director Grodecki said, “corrupts the soul”. In the opening scene of the movie, Marek and his friends smash a shiny shop window filled with goods symbolizing Western capitalism – on the background of a picture with lit skyscrapers are cans of Coca Cola, a prop of Phillips battery, and LM advertisement titled “The Taste of America” – stealing some of the items. In another scene, Marek engages in quite an explicit sex scene with an unidentified Westerner. (Before they have sex, the foreigner creates a “classic light for [Marek’s] classical body” and prompts a naked Marek to pose on a pedestal like a classical sculpture.) The movie thus expresses the fear of exploitation and a threat posed by foreign predators and foreign practices to the integrity and sovereignty of both the individual and the national body. According to Kolářová however, through its dystopic message the movie reasserts white, masculine, heterosexual, and ableist (and one may add exclusionary, or provincially, nationalist) notions of Czechness. In the end, far from a critique of capitalism, Mandragora is a warning tale of emasculation of Czech society that ends up perpetuating and upholding the neoliberal capitalist order. The remedy is not zero consumption, but orderly, moderate, and gradual accumulation.

In order to illuminate the ways in which the late 1990s affects of “bad mood” and dystopia implicitly engaged in upholding the ideological narrative of “capitalist rehabilitation,” Kolářová built on her earlier analysis of the euphoric moment of the immediate post 1989 period. As she has claimed in an earlier text, “The Inarticulate Post-Socialist Crip: On the Cruel Optimism of Neoliberal Transformations in the Czech Republic,” the dominant affective politics of post-socialism was that of “paying off” the debt of failed communism, a call for temporary austerity and gradual accumulation of resources before the country’s economy would be fully restored – and the national body whole and healthy. What this disability/crip narrative of “capitalist rehabilitation”, and the (cruelly) optimistic vision of restoration foreclosed, she argues, was the possibility of articulating critical disability/crip narratives.

Through its identification of the corrupter as foreign predators and foreign goods, crucially, Goreckis’ movies and the ensuing public discussion “whitewashed” and displaced another racialized panic around the national body: white Czech violence against the Roma. Kolářová reminded the audience that Grodecki shot some of the scenes in Mandragora in Usti nad Labem, a place of intense racial conflict in the time period, the site of a wall separating the allegedly unruly, violent, loud, big-family Roma citizens from the law-abiding, heterosexual, clean, white Czech citizens. In a moment of vulnerability rarely seen at academic talks, Kolářová’s voice faltered as she “said the names” of the Roma victims of racialized violence that have been silenced and slipped into obscurity.

Ultimately, the “ideological labor and affective attachments” of the late 1990s belong to white heterosexual nationalism. How, then, can this moment of homophobic nationalism and racist displacement be used to uncover crip narratives, narratives that do not conform to, and even critique, the rehabilitative discourse? According to Kolářová, the official stance of the organization of physically disabled Czechs was supportive of capitalist logic of overcoming or curing disability, and erasing difference; and there are virtually no personal testimonies. Without recourse to oral history, how can this deeply problematic archive be used generatively, illuminating moments of what Kolářová calls crip signing? The lecture concluded with these key questions from Kolářová, and we will eagerly await her book for the answers.

[1] Respekt, 9/1997.