Natsume Sōseki’s ‘The Carlyle Museum’ (カーライル博物館): The House Museum in the Age of Victorian Transnationalism

Lisa Hofmann-Kuroda, UC-Berkeley

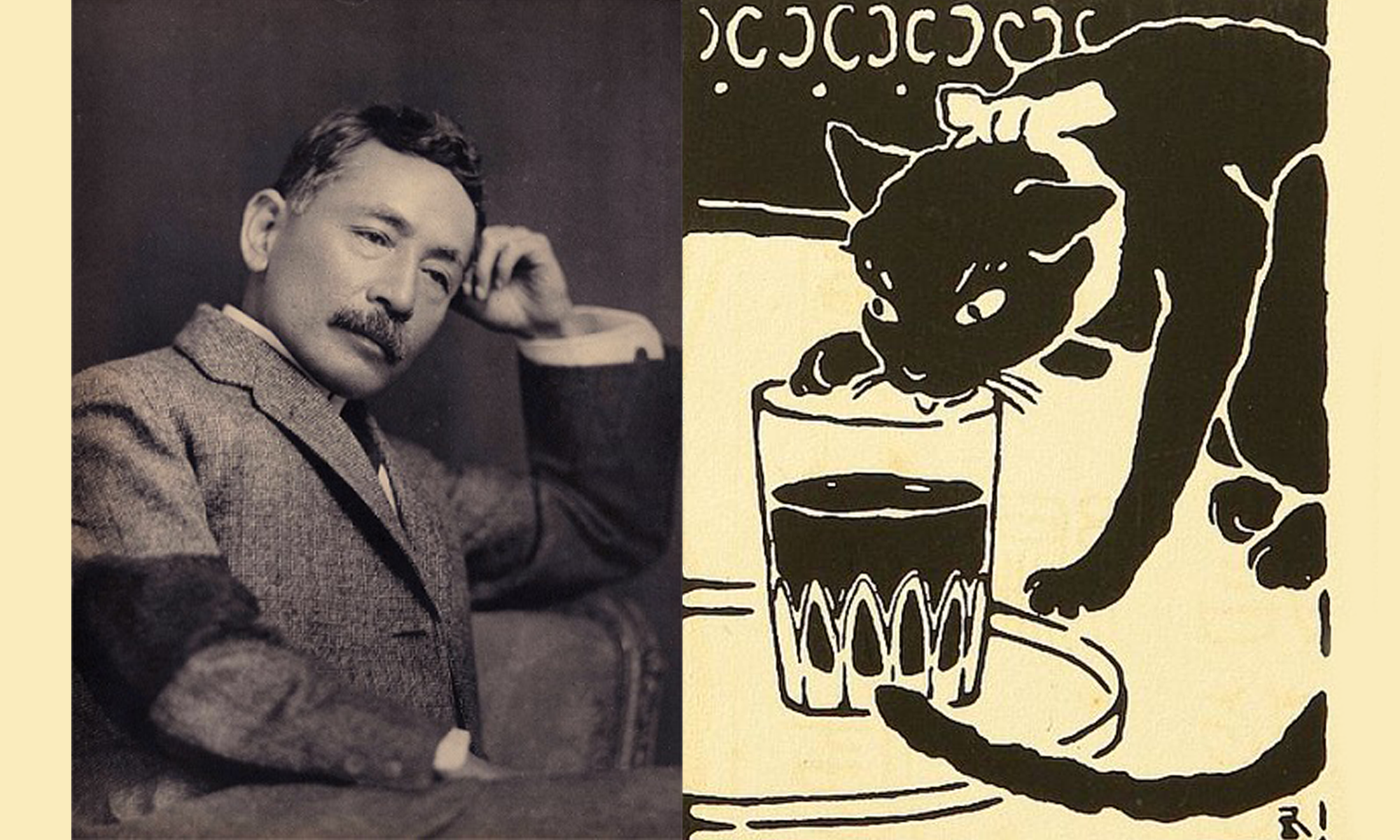

My paper focuses on a short literary sketch written early in Sōseki’s career called “The Carlyle Museum” (1906), which chronicles Sōseki’s visit in 1901 to the erstwhile home of Thomas Carlyle, a major figure of Victorian letters whose writing would subsequently influence Sōseki’s own development as a writer. Specifically, I investigate the setting of the story—the house museum—a phenomenon whereby a writer’s house was converted into a public museum after their death. Given the often nationalistic bent of these house museums, which positioned the writer as a symbolic extension of the nation, I ask what it means for Sōseki as a racialized other to inhabit such a space. I argue that Sōseki’s account of his visit to Carlyle’s house highlights the ambiguity of his position as a Japanese citizen abroad around 1900, as both a semi-colonial subject labeled as a racial other, and as an imperial agent of a rapidly growing Japanese empire. While certain passages of the story clearly call attention to Sōseki’s outsider status as a Japanese person within a British national house museum, others foreground his status as a an imperial agent who is “collecting” artifacts of British literary culture to be incorporated into a Japanese imperial project.

Sōseki | Whitman | Arishima: The Miner, the Specimen, and the Labyrinth

Andrew Leong, Northwestern University

Ken Inoue’s recent periodization of Walt Whitman’s reception in Japan begins with Natsume Sōseki and ends with Arishima Takeo. Inoue’s periodization offers the closure of a dramatic plot, where Whitmanian individualism or egocentricity (jiko hon’i) enters the Japanese stage through Sōseki’s introduction in 1892, and exits with the suicide of Arishima in 1923, an act which “in effect brought down the curtain of Whitman’s popularity in Japan.” Although this dramatic emplotment may offer a pleasing sense of closure, this method of historical ordering runs counter to the unruly and formless messiness of Sōseki, Whitman, and Arishima’s individualisms. Previous scholarship has already examined the historical trajectories of Whitmanian egocentricity in Sōseki and Arishima’s essays and speeches, but I argue that we can learn more about the anarchic force of the unplotted by turning to the “tumble” of Whitman’s prose (Specimen Days and Collect, 1882) and Sōseki and Arishima’s messiest novels: The Miner (坑夫, 1908) and Labyrinth (迷路, 1918). Such an approach works against the containments of dramatic closure and historical quarantine, allowing us to discern how the comraderies of Whitman, Sōseki and Arishima’s egocentrisms might continue to find play in our present.

Owner of a Lonely Heart: Property Trouble in Sōseki’s Kokoro

Michael Bourdaghs, University of Chicago

Part of a larger project that re-thinks Sōseki’s fiction and literary theories in relation to modern ideologies and practices of property ownership, this paper will examine his 1914 novel, Kokoro, looking particularly at the status of figures placed in contradictory positions of Japan’s modern property regime: younger brothers, women, and colonial subjects. Under the property system established by the 1899 Meiji Civil Code, itself a milestone in Japan’s ongoing project to achieve parity with the modern world powers, each of these subject positions was defined ambiguously as being simultaneously a form of property to be owned and a potential owner of property. Reading the novel in relation to the contemporary Land Cadastral survey in Korea, by which the Japanese empire attempted to reorganize the landed property system of its most recent colonial acquisition, the paper explores how Sōseki exploits the ambiguities of the new ownership regime to create his fictional narrative. In a novel whose fictional world is structured largely by an inability to speak dark secrets, by an inability to own up to past incidents, to what extent do property systems stand in for the unspeakable?

Description in the Novel: Shaseibun and Natsume Sôseki’s Narrative Experiments

Reiko Abe Auestad, University of Oslo

According to Seymour Chatman, “narrative has dual temporality, that of the sequence of events and that of the narratorial presentation, while description only has the latter.” Even though many critics over the years have nuanced this claim, the consensus seems to be that there is an impulse in description to interrupt narrative by suspending time, and one of the challenges for the realist author is not to make description a mere “filler” but an integral component of the narrative machinery itself.

The present paper will examine how this “description vs narration” binary plays out in Sōseki’s shaseibun and shaseibun features in his novelistic works. Shaseibun is inspired by Masaoka Shiki’s notion of “shasei” (prose sketch) in haiku and even though it is considered to be a variant of realism, it distinguishes itself from transparent objectivism of the 19th century Western realism. Shaseibun typically proceeds in the present tense, and does not necessarily have an unifying point of view. To borrow Karatani Kôjin, shaseibun seeks to produce an affective excess that resists interpretation (“yojō”), which is yet to settle into a meaningful pattern. Some of the questions which will be addressed are: How does it compare with novelistic techniques such as “free indirect discourse,” “interior monologues” and “stream of consciousness,” with which shaseibun seems to share certain features? What happens to the tension between narrative and description in Meian (Light and Dark, 1916) from which shaseibun features are absent.

Sōseki and Haiku

Keith Vincent, Boston University

Before Sōseki was a novelist, he was a haiku poet. He wrote more than 2500 haiku in total, more than half of which were included in private letters sent to his close friend the haiku poet Masaoka Shiki as the latter lay dying of tuberculosis. As Shiki’s disease worsened and he was no longer able to walk, Sōseki’s letters and haiku, sent first from Matsuyama and then from Kumamoto, served increasingly as Shiki’s window on a world he could no longer experience first hand. As Sōseki worked to convey the fullness of his experiences of the world to his friend, the two men carried on a theoretical discussion about techniques of description in both haiku and prose that would allow the reader to feel the same emotions as the writer experienced when he or she perceived an object or inhabited a space.

In this paper, I discuss some of the characteristics of Sōseki’s haiku and ask what difference it makes to Sōseki as a novelist that he honed his skills as a writer by writing haiku. I suggest that haiku served to sharpen and shape his powers of observation and to preserve his memories in specific ways unique to this genre. I discuss the gendered and sexual implications of genre, by considering what it meant that he wrote so many haiku in private letters to a single male friend while writing novels addressed to a public audience that included both men and women. Finally, given that Sōseki is one of many modern Japanese novelists who also wrote haiku, I ask what the practice of writing haiku might have contributed to the stylistic DNA of the Japanese novel more broadly.

This week, as I am going over page proofs for my Soseki biography, coming from Columbia in March, I am once again thinking a lot about him. Had I known about the conference, I’d have arranged to be there. I’m sure it will be fascinating.