By Elizabeth R. Gebhard

(This article originally appeared in:

Proceedings of the Fourth International Seminar on Ancient Greek Cult,

organized by the Swedish Institute at Athens,

22-24 October, 1993

Edited by Robin Hägg

Stockholm 1998

and is made available electronically with the permission of the editors.)

Abstract

After the fire that destroyed the Archaic Temple of Poseidon, a layer of burnt debris was left on the site beneath the floor of the Classical temple. A portion of the layer seems to belong to the temple treasury that included objects of precious metals and gems that had been stored in one or more wooden chests. While the majority of the 500+ items recovered represent dedications, only the smaller pieces survived intact. Fragments of large bronze vessels and utensils appear to be the remains left behind after most of the metal was salvaged for melting and recasting. In time, the objects range from the early 7th to the early 5th century with a concentration in the second half of the 6th century B.C. In type, they represent personal possessions of athletes and warriors, women, craftsmen and fishermen, while a few figurines and tripods were made for dedication. In Appendix A, Julie Bentz discusses the ceramic evidence for the date of the fire; Appendix B contains a table illustrating the distribution of objects by type within the burnt layer.

An intense fire brought down the first temple of Poseidon on the lsthmus of Corinth, but the area was soon cleared and a new temple constructed on the same site (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Restored plan of the Isthmian sanctuary, ca. 400 B.C., showing the Archaic temple and areas of debris in which small dedications have been found

While most of the wreckage was removed and almost no building block was left in place, a layer of debris remained as fill beneath the floor of the Classical structure. Building and other activities in later times disturbed much of the deposit, but four small sections of it in the eastern and southeastern parts of the temple appear to have survived largely intact. A brief survey of objects from these four areas is presented here in order to show the range of things that were stored in the temple at the time of the fire.1 Not all of them need to have been dedications, although most probably were and hence the title. In In Appendix A, Julie Bentz analyzes the latest identifiable heavily-burnt sherds to arrive at a date of ca. 470-450 B.C. for the fire. Appendix B contains a table showing the distribution of objects between the four deposits.2 Some tentative suggestions are made concerning the disposition of offerings within the temple.

History of excavation

When Oscar Broneer began excavation of the Temple of Poseidon in 1952, the modem field lay no more than about 2 m above the surface of the plateau on which the temple was built. In the upper deposits, architectural elements of the Classical building were found mixed with small fragments of marble from the inscriptions, reliefs, and statues that were presumably in the temple when it was dismantled in the early 5th century A.D.3 As clearing progressed, there appeared small limestone blocks with grooves for ropes and roof tiles of a very early type. At the time, Broneer reported: “Though none of the blocks were found in situ, they seem to have been used as fill beneath the floor of the temple, and it is likely that they belong to a predecessor of the Classical building.”4 In the final publication of the temple, however, he did not discuss the excavation. He simply stated that there was “no stratigraphic evidence of importance for dating” and placed the fire that destroyed the Archaic temple in the period of the Persian Wars.5

For a detailed account of the deposits in the temple it is necessary to consult the field record for the 1954 season. The trench supervisor, Gustavus Swift, at an early stage of his work, identified as an “Archaic deposit” areas of soil, ash, and carbonized wood that were mixed with broken Archaic roof tiles, burnt mud brick, and “nests” of small Archaic objects of a votive character. At the end of the season, Swift outlined the sequence of excavation with the comment that “clear recognition of the ‘Archaic deposit’ began (for me at least) with the discovery of silver coins in [Trenches] C-6, C-8 … From then on Archaic fill was deliberately and carefully excavated in various spots in [Trenches] C-3, C-6, C-8.”6 It was the concentration of carbon and the firmness of the matrix in each case that. enabled him to distinguish the Archaic deposit from the surrounding area. He sifted the soil and meticulously described its contents, including the burnt mud brick, small bits of carbonized wood, and fragments of Archaic roof tiles.7 Of the six areas he lists as part of the “Archaic deposit”, four are analyzed here under the headings A, B, C, and D. The two small areas in Swifts “Archaic deposit” that are not included were less clearly defined and add little to the general picture.8 Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the location of Deposits A-D within the temple.9

They are not contiguous, and B had a different depositional history from the others (see “depositional history” below). On the other hand, A-C probably belonged to the same layer of debris.

Figure 3. Restored diagram of Deposits A, C, D, outlined in dashed lines, looking west; adapted from Notebook 4, p. 164. (Pieter Collet)

While it is difficult to reconstruct an old excavation from the field record, especially when the people involved are no longer available for comment, the clarity of Swift’s observations and the precision with which he registered the objects inspire confidence in the accuracy of his recording and the validity of his conclusions. It is for this reason that it seems right to follow him in concluding that the four burnt deposits represent debris from the Archaic temple and present evidence for the contents of the temple at the time of the fire. None of the deposits was sealed, however, and a few small pieces of much later material entered them at some time before they were excavated (Appendix B).

Deposit A, measuring ca. 2 by 4 m, was 0.24 m deep at the east end and tapered to 0. 12 m at the west (Figure 3). It lay within the pronaos of the Archaic temple and contained the largest number of artifacts. Apparently unstratified, it was excavated in two equal strips, beginning at the south side.10 Deposit B lay within the foundation trench for the pronaos columns of the Classical building, under a nest of broken marble floor slabs from Roman times. It is the largest of the four units, covering an area of a little over 3 by 5 m and with a depth of ca. 0.70 in.11 Deposit C, measuring ca. 1.30 by 3.50 in, lay on a small island of soil between a disturbed deposit that filled the foundation cutting for the center columns of the Archaic pronaos and the foundation trench for the south wall of the Classical cella.12 Deposit D was the only deposit from the cella of the Archaic temple. It formed a ridge between the foundation cutting for the south wall of the Classical cella and the temple’s southern interior colonnade. The former foundation cut through most of the trench for the south wall of the Archaic cella, and the latter lay on the same line as the center columns of the Archaic temple. D stretched for 10.50 in east-west through the cella and it was ca. 2 in wide by not more than 0.50 in deep.13 Two layers were defined; the upper contained less burnt material than the lower. They were cleared separately.

Depositional history of A-D

Deposits A-D do not represent the debris as it lay in the temple immediately following the fire. Before the Classical temple covered them, they were shifted and some of their contents seems to have been removed (see “composition” below). The yellow, sandy, almost sterile soil below A, C, and D is not compacted and cannot be the floor of the temple.14 It is not later than the temple, however, since nothing post-dating the fire was found in the portions excavated in 1989. The high proportion of sand and the presence of stone chips suggest that the layer served as a bedding for a stone floor. The slabs would have been removed, together with the foundations of the walls and stylobate, after the destruction.15

A schematic, hypothetical reconstruction of the scene during the fire suggests that the interior of the structure would have been a mass of charred objects over which fell the ceiling, beams, and heavy tiles when the roof collapsed. The upper parts of the walls probably came down as well; the wooden columns were presumably consumed in the fire. The clean-up crew would have begun with the stones and then worked their way down through the charred wood, mud brick, and roof tiles before coming to the contents of the interior. They apparently piled the building debris near the site, because the terrace and road fill that were its final destination were not built for another 10-20 years.16 When it came to sifting through the contents of the temple, objects of value were removed, including the floor slabs. The residue would have been the layer of burnt material, including building debris, that remained as a bedding for the floor of the Classical temple. Deposits A-D belong to that layer.

Deposit B, probably originally contiguous to A and C, shifted in Late Antiquity to the footing trench for the stylobate of the pronaos columns in the Classical temple. It could not have come there before the foundations were removed but slipped down when the blocks were hauled away towards the north. A deposit of similar composition and depositional history, but including sherds post-dating the fire (Pottery Lot. 58 and associated objects), was excavated in the bedding for the center columns in the Archaic pronaos, between Deposits A and C and labeled “disturbed area” in Figure 3.17

Figure 3. Restored diagram of Deposits A, C, D, outlined in dashed lines, looking west; adapted from Notebook 4, p. 164. (Pieter Collet)

When they were laid down, Deposits A-C together with the burnt fill containing Pottery Lot 58, probably formed a single layer of debris within the Archaic pronaos.18 A connection between A and B is strengthened by the fact that pieces in both deposits came from the same object or set of objects, such as identical gaming-pieces, fragments of a tortoise carapace , and bars possibly from a rod tripod. Non-joining fragments from the rim of a bronze pail link B and C; silver coins were found in A-C with the major concentrations in A and B (Appendix B). There are, however, no such similarities between A-C and D. The latter deposit with a couple of exceptions contained objects of a larger size and of a type that would have been stored in the cella rather than the pronaos.

All of the deposits contained clusters of small artifacts of similar types, such as aryballoi, hand-made jugs, weights for a fishing net, coins, chariot fittings, jewelry, and scarabs. Swift described them as “nests” and mentioned that they were often tightly packed together with bits of carbonized wood and burnt mud brick. Thus, although the burnt layer was disturbed during the clean-up and reclamation activities after the fire, it was not scattered, and sections of it slipped gently from one surface to another as blocks were removed. A further indication that the deposits were not much disturbed after they were laid down is the fact that some of the small vases remained virtually intact or their pieces were found in the same area (e.g. the globular lekythos in Figure 6b, a beaked oinochoe, and miniature krater).

Other vessels were broken during the clean-up and some of their fragments carried away to be deposited in the east temenos (e.g. a palmette skyphos and Attic white-ground lekythos). A related question concerns the extent to which the objects were moved from their original locations within the temple at the time of the fire. The clusters may reflect the pattern of storage, or, less likely, sorting during salvage operations. While there are reasons to believe that the small and valuable objects in Deposits A and B (coins, jewelry, gold figurine) came from a treasury in the pronaos, other locations are possible.

Finally, for those who may argue that it is impossible to be certain that the artifacts and burnt building debris were not introduced into the temple after the fire, we note that it is highly unlikely that loads of soil mixed with bits of carbonized wood, ash, Archaic roof tiles, mud brick, and small objects of a votive character would have been transported into the building, when the vast majority of such material was being carried out of the area for disposal elsewhere.

Composition of A-D

There is a conspicuous lack of metal objects, especially bronzes, and the fragments of heavy castings show signs of having been intentionally broken. Some pieces of thin bronze sheet have been folded over two and three times so that they are comparable in size to the castings, about 0.03 by 0.07 in. Similarly broken and folded bronze pieces occurred in other deposits of debris inside and outside the temple, together with risers, pouring tubes, drips, and spoiled castings that betray the presence of foundry activity in the area.19 It seems likely that, after the fire, much of the damaged bronze from the Archaic temple was salvaged and reduced to pieces of a suitable size for remelting. The tools in the temple may be related to salvage activities, although they could equally well be dedications. Other materials belonging to workshop activities include small stone blades, lumps of red ochre, the base of a cup used as a palette, and thin sheets of gold, silver and bronze. The gold and silver leaf, along with red ochre used for applying gold leaf, may also have belonged to the temple stores, perhaps for repairing precious dedications.20 It is impossible to know how many valuable objects, such as coins and jewelry, were reclaimed from the debris after the fire, and likewise, why some valuable objects remained behind. The reason could be simply oversight on the part of the workmen, or possibly an intentional deposition of a remnant of the god’s possessions in his new temple. Thus, the burnt deposits were not closed immediately following the blaze but sometime later after a period of salvage, during which time reusable metal and other valuables were removed.21

The total number of items reaches over 508, exclusive of the context pottery, Archaic roof tiles, fragments of blocks, and other building debris. Single sherds probably found their way into the temple during its use, since they predate the fire and a number are burnt. They are largely Archaic (ca. 2,450 sherds), with 15 Mycenaean pieces and 30 from the Early Iron Age.22

Date of the Deposits

That the final deposition of the four deposits was not contemporary with the burning of the temple has been noted above. The closing date very likely falls somewhere near the end of the 5th century.23 From Deposit B two small bronze coins of the Pegasus-Trident series (IC 265, 265 bis) probably belong to the period of cleaning up after the fire. The starting date of the series has recently been moved back to the late 5th century on the basis of material from the Corinth excavations. The weight of the only complete example of the two would place it at the beginning of the period.24 Among the 128 silver coins, only a silver diobol in Deposit C may have been minted after the fire, between 450 and 430.25

Since the deposits were covered only by the floor slabs of the Classical temple, a small amount of later material entered them, perhaps during renovations or after the final dismantling of the building (Appendix B). Most pervasive were tiny fragments of Roman plaster, some bearing red paint on one face. In Deposit A were a small fragment from the base of a Roman glass vessel, two small marble chips, and a sherd from a relief vase of ca. 200 B.C.

The fire that destroyed the Archaic temple seems to have taken place between ca. 470 and 450, probably close to the middle of the century. The four latest burnt sherds are discussed by Julie Bentz in In Appendix A.26

Dedications

A thorough discussion of the dedications, including the iconography and parallel examples from other sanctuaries, will be included in the final publications. In this paper, the objects are listed in summary fashion as an example of the contents of the temple at the time of the fire. The objects are grouped according to their type and possible function in the temple: coins, figurines, athletic equipment, tripods, bronze vessels and utensils, arms and armour, ceramic vessels, jewelry, various small dedications, tools, objects related to wooden constructions, and raw materials. Appendix B presents the distribution by deposit.27

A. Coins

Of the 128 silver coins, 61 came from from Aegina and 57 from Corinth; three coins are Argive, two Boeotian, and one each came from Sikyon, Eretria, Skyros, Naxos, and Miletos. The earliest coins are dated ca. 550 and the latest are two small Corinthian Pegasus-trident bronzes that probably belong to the second half of the 5th century.28

As Broneer concluded, the silver coins do not appear to have been a hoard in the sense that all of them were deposited together at the same time but rather to have belonged to the temple treasury. They may have been dedications offered over a period of years or they may represent a portion of the revenues paid to the sanctuary. In any case, the burning of the Archaic temple would have marked the end of the collection.29 The greatest concentration (61 %) occurred in Deposit A where coins were found mingled with jewelry and other small objects.30 None came from D. The coins, then, seem to have been stored with the jewelry and other small valuables in the northern half of the pronaos. There they escaped the heat of the fire. Most of them show no trace of burning.

B. Figurines

A bronze satyr and nymph, badly damaged, were found together in A and seem to have formed a pair representing an abduction. They are too poorly preserved to tell how they were supported, but they may have formed the handle on the lid of a bronze dinos.31 Three other anthropomorphic figurines left only one arm a piece in A and B. One of them, a wreathed, nude male, probably an athlete, was found in the fill of the east terrace ca. 40 m away.32 The bodies of the other two have not come to light. The sculptures of three bulls are complete. One of bronze and a miniature of gold only one centimeter long (Figure 4) were free-standing on their base plates.

The third bull, its lower legs broken off, may have come from a tripod.33 The object, a century older than the rest, could have been an heirloom when it was dedicated, or it could have been set up outside in the temenos and later stored in the temple. In any case, the bull is the earliest object in the layer of debris, with the exception of the Mycenaean and Early Iron Age sherds, and it pre-dates construction of the building. Only the satyr and nymph show signs of exposure to intense heat. They could have been detached from their vessel before or after the fire, which is true also of the early bull. The gold bull, however, must have been well insulated from the fire, since gold has a low melting point and its surface is perfectly preserved.

Terracotta horse-and-rider figurines are not well-represented in the temple, although they are the most common dedication at the sanctuary. Most of them occur in the east temenos, many near the long altar where they may originally have been dedicated.34 The four or possibly six small fragments in the temple deposits could have come into the building already broken in the same manner as sherds of pottery, or the complete figurines may have been stored there.35 A faience figurine with traces of green glaze perhaps represents a two-legged animal.36 It very likely came from Egypt, as did the faience scarabs discussed below in Section H.

C. Athletic equipment

The group includes bronze strigils, iron sockets possibly for javelins, and most interestingly, the iron clamps and rings from one or two racing chariots.37 The number of vehicles represented is uncertain, but six clamps and a rod with ring came from Deposit A, and B held another rod and ring.38 In the road fill at the north side of the temenos (north temenos dump) clusters of three and four clamps were also found together in a way that suggests that each group came from a single chariot.39 In D there was an iron rim or tire from the outside of a wooden wheel, together with a clamp of the type found in A (Figure 5).40

The wheel could have belonged to a chariot or a cart. Dedications of wheels and complete chariots at sanctuaries are attested. On a well-known early Apulian krater in Naples the interior of Apollo’s temple at Delphi is represented with wheels and helmets fixed to the wall.41 Also at Delphi, Pindar (Pyth. 5.43-54) describes the charioteer, Carrhotus, dashing from his victory in the hippodrome to hang up his chariot under a shelter of cypress wood in the sanctuary.42

D. Tripod?

Six bronze bars from Deposits A and B may have fitted between the looped rods near the top of a rod tripod.43 The bars, if indeed they do belong to a tripod, together with the bronze bull perhaps from an early Archaic tripod, constitute the only evidence for tripods inside the temple at the time of the fire. In the 7th century, however, a large iron tripod stood in the eastern peristyle. Broneer found the lower ends of its legs embedded upright in the earliest floor.44

E. Bronze vessels

The small fragments of vessels in Deposits A and B that can be identified include cast handles, terminals, decorative attachments, the rim of a pail, the foot of a small hydria, ladles, and the ring from the lid of a pyxis.45 The bronze vessels and implements appear to have been intentionally broken, probably in preparation for re-melting and re-casting.46 All of them belong to the Archaic period.

In the northern half of Deposit A was a cluster of three identical mouths from bronze lekythoi; another such mouth was excavated in the southwest corner of the cella and three more in the east terrace.47 The shape is rare in metal, but it seems to have been especially popular among Isthmian dedications, The cluster is similar to the groupings of aryballoi, mugs and jugs described below and suggests that they had been stored together in the temple

The rim of a pail bears a dedicatory inscription to Poseidon that Professor Raubitschek restores as ![]() ; the order of the words is not certain.48

; the order of the words is not certain.48

F. Arms and armour

Poseidon received a very large number of arms and armour, but the place of display in the sanctuary is not altogether clear. Most of the material was recovered from the Classical road bedding at the northwest side of the temenos. Alastar Jackson points out, however, that it would have been difficult to erect wooden posts for its display along the road because of the rocky surface surrounding the shrine and no suitable post holes have been uncovered.49 That military equipment was in fact dedicated in the Archaic temple is shown by the presence of two small pieces from Corinthian helmets and an iron staple that may have been attached to a helmet for suspension. The debris layer in the temple also held the bronze toggle from a sword belt and a bronze arrowhead.50 A similar staple, still attached to a piece of bronze sheet, was found in the northwest road fill, also in conjunction with the toggle for a sword belt.51 Remains of more helmets came from mixed deposits in the west half of the temple. The helmets and arrowhead belong to the end of the 6th or early 5th century.52

G. Ceramic vessels

Only vases preserving a substantial portion of the profile are included in the list given below and summarized in Appendix B. Other vessels may well be represented by the sherds in the debris, but further study is necessary before the full range of types and quantities can be set forth.53

SINGLE VASES

a. Small, broad-bottomed oinochoe (IP 1293 E; Figure 14); probably not much before 460 (or later); see In Appendix A, 1.

b. Attic palmette skyphos (1]? 6750a-c; Figure 17); Hermogenean type; ca. 480-475; with joining fragments in the cast terrace (Trs. EC-C, D, E). See In Appendix A, 4.

c. Beaked oinochoe with strainer neck, almost complete (lP 325); early in the third quarter of the 6th century. Fragments in Tr. C-7, mixed context, just east of Deposit A.

d. Powder pyxis (lP 344); near the middle of the 6th century.

e. Miniature krater (lP 347); almost complete; second half of the 6th or 5th century. Many miniatures were recovered from the east terrace.

f. Fragments of an Attic white-ground lekythos with figures of Athena and Hermes, (IP 360, joining IP 7553 in the east terrace (Tr. 89-3); IP 361 with joining fragments in nearby Tr. C-7); first quarter of the 5th century.54

g. Kotyle (lP 326), burnt; first half of the 5th century (Figure 6a, left).

h. Globular lekythos, complete (IP 332); ca. 480-470; half of the body burnt (Figure 6b, right).55

i. Saltcellar (IP 6902). Corinthian imitation of an Attic type, belonging to the late 6th or early 5th century. j. Two plastic vases (IP 329, 349); 6th century.56

CLUSTERS

Three types of small vases were particularly favored at Isthmia, and they were apparently stored together in the temple. In Deposits B and C were nests of aryballoi (Figure 7a-e)

57 and black-glazed, single-handled mugs (In Appendix A, 3, Figure 16);58 in D were clustered small hand-made, undecorated jugs (Figure 8a-c).

One large black-glazed, Attic mug is decorated with a scene of fighting warriors in red-figure technique and it bears a dedicatory graffito neatly incised on the rim, ![]() .60 The mugs belong to the late 6th and 5th centuries, while the aryballoi are much earlier. Five aryballoi go back to the last quarter of the 7th century, and the rest belong either to the late 7th or the first half of the 6th century. They include examples of Laconian and East Greek manufacture.61 The small hand-made jugs stand in marked contrast to the elegant aryballoi and black-glazed mugs in their mode of manufacture and lack of embellishment. They may be simple, personal possessions, but they may also have had some special function in the sanctuary. Similar vases occur in the Early Iron Age both at Corinth and at Argos where they are often found in graves.62 The number of specimens in D, together with examples outside the temple, indicate that the small, hand-made jug was a favorite offering at Isthmia.

.60 The mugs belong to the late 6th and 5th centuries, while the aryballoi are much earlier. Five aryballoi go back to the last quarter of the 7th century, and the rest belong either to the late 7th or the first half of the 6th century. They include examples of Laconian and East Greek manufacture.61 The small hand-made jugs stand in marked contrast to the elegant aryballoi and black-glazed mugs in their mode of manufacture and lack of embellishment. They may be simple, personal possessions, but they may also have had some special function in the sanctuary. Similar vases occur in the Early Iron Age both at Corinth and at Argos where they are often found in graves.62 The number of specimens in D, together with examples outside the temple, indicate that the small, hand-made jug was a favorite offering at Isthmia.

It is perhaps surprising to find that at least one Corinthian A amphora was stored in the temple at the time of the fire. Although no example has been mended, sherds weighing over 2 kilograms were recovered from Deposit D. The fragments have their inner surfaces burnt to such a degree that the clay is vitrified. The amphoras evidently held olive oil that was ignited by the fire, and the beat was such that it melted the inside of the vessels.63

H. Jewelry

The jewelry consists of very small pieces concentrated in Deposits A and B in the same clusters as the silver coins (Appendix B). One might suppose they were left behind when larger and more valuable objects were retrieved from the debris. The types include finger rings, a finely carved sealstone, earrings, straight pins, and beads of gold, silver, bronze, iron, faience, and carnelian.

Finger rings are the most numerous, but the small size and quantity of the fragments make it impossible to arrive at a precise number.

a. Silver ring with incised griffin on bezel (complete).64

b. Silver band (complete) and fragments of five others.65

c. Six complete bronze finger rings.66

d. Iron finger rings, 27 complete, 169 fragments.67

A single gemstone bears the incised figure of a nude youth running to the right (Figure 9).

He holds a flower to his face in his left hand and in the right he grasps what looks like a loop of string.68 The gem is pierced lengthwise, but no mounting for it was found.

Three pairs of silver earrings can be distinguished, although they are poorly preserved.69 Of the pins, five are simply made of bronze.70

More spectacular is the delicate terminal fabricated of gold leaf in the shape of an elaborate pomegranate.71

A set of seven almost identically carved carnelian beads are pierced at the top for stringing on a necklace (Figure 10).

One or more necklaces are represented by the single gold, silver, and bronze beads and five faience beads.72

Fragments that might have belonged to jewelry include a bronze hoop, a flat ornament composed of tiny silver beads in concentric rings, and bronze beads joined together.73

I. Miscellaneous small objects, probably dedications

The following small and exotic items were all found in Deposits A and B with the jewelry and silver coins. They strengthen the impression that the assemblage had once belonged to the temple treasury.

Imports are relatively rare at Isthmia, but the temple held several things of Egyptian origin, principally three faience scarabs and six fragments of faience that may be the remains of other scarabs (Figure 11).

The hieroglyphs on two of the scarabs are mottoes conveying the protection of Re and Re and Horus. The third is a design scarab.74 Travelers may have carried them as amulets and then dedicated them to Poseidon after a safe journey. Other possible amulets are a Red Sea cowrie shell with a ground-down dorsum (Figure l2e) and a piece of natural white coral.75 Also of faience with a blue-green glaze, similar to the scarabs and thus probably from Egypt, are the animal figurine and five beads mentioned above.

Fragments of a tortoise carapace, that included one with a drilled hole, very likely came from the lower part of a bowl lyre. The instrument could either have been a lyra that was played by both men and women, being “the ordinary instrument of the non-professional”, or a barbitos that seems to have been been favored at drinking parties.76

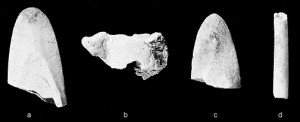

Eight small cylinders carved from bone clearly formed a set. The tops are domed and the bottoms are flat and incised with two pairs of concentric circles around a center point (Figure 13).

Their uniformity, small size, and the circles on one end make it likely that they are gaming pieces from a board-game and were dedicated as a group.77

A small, round piece of black stone with incised, Geometric decoration on one face and a pierced knob on the reverse may be a button seal of the late 7th century.78 A small bell of terracotta came from Attica.79 Finally, there were two worked bone implement ends (Figure 12 a, c),

a holed sheep or goat astragalos (Figure 12b), and four bone pins (Figure 12d), all of them burnt.80 Holed astragaloi are usually found in graves and in sanctuaries where they may have been used for divination.81

J. Tools

The 13 tools were more evenly distributed among the deposits than the small objects of value (Appendix B). Two of them could have had no other function in the building than as dedications: an iron fishing spear and a set of 12 lead weights from a fisherman’s net.82 A well- preserved and complete iron knife with a decoratively attached hilt came from Deposit D, together with the iron wheel rim and the silver ring with an incised griffin. The blade might have been used in sacrifice before being dedicated.83 Two iron chisels and an ax-adze could have been workmen’s gifts, or they could have been used in salvaging activities.84 Four smaller iron blades and two flaked stone blades also occurred in the deposits.85

K. Objects related to furniture and other constructions

The surviving metal elements of wooden construction were concentrated in Deposits A and B. The 17 nails and tacks could have belonged to tables, shelves, or chests,86 as also a solidcast bronze foot in the shape of a lion paw.87 Four iron bosses are of a type and size that was often found on doors, but they also ornamented chests.88 A strip of bronze beads could have been used on furniture.89 More elegant are two gold studs with prongs for attachment,90 a silver rosette, and a cap-shaped ornament.91 Several bronze and iron rings could also have been attached to chests.92

L. Raw materials

Objects related to workshop activity include the base of a cup stained with red miltos,93 broken fragments of heavy bronze castings, folded pieces of bronze sheet,94 very thin sheets of gold, often folded,95 and pieces of red ochre, one with a fragment of gold sheet embedded in it. Red ochre was used as a base for the application of gold overlay.96

Conclusion

The small, valuable objects in Deposits A and B may be the remains of a treasury deposit, as Broneer suggested, although it cannot be certain that the material was not shifted after the fire. What does appear likely is that the clusters of small objects reflect the pattern of their storage in the temple. The metal fittings found with them could well have belonged to the wooden chest(s) in which they had been kept.97 As noted above, the gold objects in particular, since they are intact and show no signs of melting, must have been protected in some way from the intense heat of the fire. The figurines and vases could have been displayed on wooden tables and/or shelves.98 Helmets, athletic gear, the fishing net with weights, and the racing chariot(s) would have hung on the walls.99 The pronaos was 6.50 m square and would have afforded ample space for the material. If it was indeed used as a treasury in the final days of the temple, there would certainly have been a barrier at the entrance that was kept locked.100

Although many fewer objects were found in Deposit D than in A-C, most of them were complete and they represent the same types. The chariot wheel would have hung on the wall. The smaller things, finger rings, sacrificial (?) knife, and the many small, hand-made jugs, could have stood on shelves or in a chest.

The chronological span represented by the objects that can be externally dated runs from the latter part of the 7th century to the time of the fire, with the exception of the bronze bull from a tripod (?) that belongs to the very early 7th century. The types of gifts that Poseidon received tells us something of the donors: women who left their jewelry, warriors’ booty taken from the enemy, athletes’ equipment after successful competition, the tools of craftsmen and fishermen, rich and poor.

The fire that destroyed the temple occurred between ca. 470 and 450, probably towards the end of the period. The area was then cleared of most of the debris and valuable items were salvaged. A thin layer of burnt material remained on the site and was covered by the floor of the Classical temple.

Elizabeth R. Gebhard

Balcanquhal House

Glenfarg

Pertshire PH2 9QD UK