The Patriotic Gurudev: Tagore’s Nationalism

ESSAY by Anurag Advani

The last sun of the century sets amidst the blood-red clouds of the West and the whirlwind of hatred.

The naked passion of the self-love of Nations, in its drunken delirium of greed, is dancing to the clash of steel and howling verses of vengeance.

The hungry self of the Nation shall burst in a violence of fury from its shameless feeding.

For it has made the world its food.

And licking it, crunching it and swallowing it in big morsels,

It swells and swells

Till in the midst of its unholy feast descends the sudden shaft of heaven piercing its heart of grossness.

-Extract from Rabindranath Tagore’s poem, “The Sunset of the Century” (1899)

This poem was written on the last day of the nineteenth century. Following this first stanza, it goes on to lament the plight of Tagore’s motherland. In it, he notes that human greed, manifest in the “self-love of the Nation”, is responsible for the crimson light on the horizon that indicates a burning pyre instead of a peace-filled dawn. He pleads to his country to be content and embrace humility, non-aggression, and meekness. He views these as the antitheses of nationalism, which symbolizes, pride, power, and aggression for him The poem ends on this note—“… know that what is huge is not great and pride is not everlasting.”

It is intriguing that someone who is considered by many to be among the most accomplished Indians ever, felt so disillusioned by the nationalist struggle as to have penned this tirade against nationalism. What led the first Asian Nobel Laureate and first Indian to be knighted to turn against the “nation”? How did nationalism become anathema to the poet who was his nation’s pride and joy? Why for Tagore did nationalism imply complete annihilation of world peace? Why did Tagore identify pride in one’s motherland with carnage, destruction, and gore? How did this become the rallying point around which the disagreement between Tagore and Mahatma Gandhi centered? These are the questions that this essay attempts to address.

I

Tagore’s views on nationalism can only be understood by first arriving at a generic definition of the “nation” and then of “nationalism”. It has been admitted by many scholars over the decades that the term “nation” was not, is not and will likely not ever be able to lend itself to a concrete, tangible form. At best, one can agree with Benedict Anderson’s classic phrase, “imagined community”, which posits the idea of a “community” as an intangible, malleable and above all fictional social construct that is the product of a specific stage of human development. Mohammad Quayum, collating from many sources, states, “Nationalism as a political expression, with people sharing a common geographical boundary and some unifying cultural/political signifier is relatively new, although cultural nationalism has prevailed since the beginning of society.” The origins of nationalism are, therefore, fairly modern. While Anderson pins its emergence to the period of 18th century Enlightenment, when rationalist, secular thought came to acquire political shape, Ernest Gellner associates it with the growth of industrial capitalism, and Timothy Brennan attributes it to the literary wave in the 19th century, especially the rise of the novel.

It seems appropriate to begin by analyzing the text for which Tagore was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1913. “Gitanjali”, or “Song Offerings” (in English translation), is undoubtedly Tagore’s most famous work. May Sinclair opines that the poems in this volume were reflective of a united emotional appeal made “in a music and a rhythm many degrees finer than Swinburne’s—a music and rhythm almost inconceivable to Western ears—with the metaphysical quality, the peculiar subtlety and intensity of Shelley; and that with a simplicity that makes this miracle appear the most natural thing in the world.” Sinclair surmises that the poems offer a degree of subtlety that can only be achieved in a rich, textured language like Bengali. For her, the spirituality of the songs of divine love in the text cuts across national barriers and unites the world in its appeal for bridging the great “gulf fixed between the common human heart and Transcendent being”. The introduction to this text was written by the renowned Irish poet-playwright, W. B. Yeats, who was also Tagore’s close friend. According to Yeats, in this volume, poetry and religion chorus in unison and the poet, in his attempt to discover the soul, surrenders to its spontaneity. Nature comes to symbolize a child-like innocence that bespeaks the beauty of God’s creation.

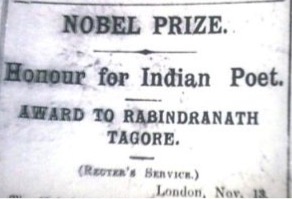

Telegram reporting receipt of Nobel Prize in Literature by Rabindranath Tagore

(Source: Reuter’s, London, Nov 1913)

The most popular reference to nationalism in “Gitanjali” is undoubtedly Tagore’s renowned poem, “Where the Mind is Without Fear”. Though written as a prayer, it is a manifestation of the idealist in Tagore, bringing out his longing for true freedom. He focuses on liberation through education, which introduces reasoning, honesty, and rationality. But most of all, he envisions a truly global society that is not fettered by any petty divisions of parochialism, domesticity, or tradition (“Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls”). Another poem that reflects Tagore’s reaction to nationalism is one that records a conversation between a prisoner and his master (probably a metaphor for humans and God, respectively). The prisoner laments, “I thought my invincible power would hold the world captive leaving me in a freedom undisturbed.” Yet another manifestation of this attitude is Tagore’s statement, “On the seashore of endless worlds children meet. The infinite sky is motionless overhead and the restless water is boisterous. On the seashore of endless worlds the children meet with shouts and dances.” What comes through is an understanding of the world as one, where nationalism hinders rather than encourages human agency and freedom.

Published in 1918, Tagore’s tract on the subject, laconically titled “Nationalism”, was a testimony to Tagore’s engagement with political affairs, attempting to debunk the criticism that he was only concerned with socio-cultural and economic developments. The gist of the argument comes through in the prophetic statement, “The Nation is ruling India”. He identifies the chief problem in India as being a racial divide and a dehumanizing classification of society that deems some inferior to others. It had dealt with this deterrent compassionately and humanely for fifty centuries, up until the time the West “burst in” and imposed its ideas and institutions on the Indians. Tagore’s perception of nationalism in the West is one of scientific precision and mechanization that results in “neatly compressed bales of humanity which have their use and high market value”. He defines it in terms of an orderly union of politics and commerce in which “a whole population assumes when organized for a mechanical purpose”. For him, commitment to nationalism leads to shunning of moral responsibility that makes men lust for power, and their duties to their family begin to come secondary.

An interesting section in the text that is worth some discussion is a chapter on nationalism in Japan. Tagore lauds Japan for breaking out of the shackles of its old habits and debunking the Western stereotype that Asia lives in the past. He points out that Japan did not merely imitate the West or blindly adopt its mechanized model. Indeed, he believes that Japan is a remarkable amalgamation of the old and the new that has managed to embrace modernity while retaining a firm hold on its ancient traditions. The spiritual and humanistic civilization of the East was perceived as being metaphysical and incapable of progress by the West. This latter notion was proved a fallacy by Japan’s climactic rise to prominence, and Tagore felt it was the beacon of light for Asia. He argues that Japan is more human and soulful that any European nation, but states that it must hold its own against the tide of Western domination. Tagore argues, “True modernism is freedom of mind, not slavery of taste.” Japan, according to him, was faltering in aiming to compete with the Western countries on their terms. They admitted “Japan’s equality with themselves, only when they know that Japan also possesses the key to open the floodgate of hell-fire upon the fair earth whenever she chooses, and can dance, in their own measure, the devil dance of pillage, murder and ravishment of innocent women, while the world goes to ruin.” Tagore was warning Japan against excessive European influence.

II

Tagore wrote that nationalism is “a cruel epidemic of evil . . . sweeping over the human world of the present age and eating into its moral fibre.” This conviction emerged out of his strong belief that the West must envisage a bridge with the East, and that only through a convergence of the two would world peace be able to prevail. This view was sharply criticized by his European contemporaries, Georg Lukacs and D. H. Lawrence, in whose eyes the West was inherently superior to the East, and hence for them the fusion of the two was impossible. But it was precisely this contempt that the West had for the Orient that irked Tagore so much. In his novel “The Home and the World” (1915), Tagore challenged this Western notion of the “nation”. This “forcible parasitism”, according to Tagore, went against all that philosophers through the ages had done for the sake of global peace. The argument came back full circle to what the protagonist in the novel says—“It was Buddha who conquered the world, not Alexander.”

This still does not explain why Tagore did not identify with nationalism as a burgeoning ideology. Some historians have argued that Tagore was a true Romantic who believed in “creation over construction, imagination over reason and the natural over the artificial and the man-made”, according to Mohammad Quayum. For him, worship of the nation above all else leads to a kind of “othering” that incites hatred and even war between countries. He saw a parallel between imperialism and nationalism, perhaps drawing on British colonization that sought to disingenuously justify the dominance of the colonizers over underdeveloped regions not powerful enough to express their resistance. Further, he perceived nationalism as an artificial creation that stifles human emotion. It is a manifestation of the industrial process that sacrifices the moral man for an immoral, greedy one who is entangled in the quagmire of politics and commerce.

However, this does not imply that Tagore did not seem himself as an Indian, or was not proud of his country. Far from it; he wrote numerous odes to his motherland and his nation. One of these, entitled “Bharat Tirtha” (“The Indian Pilgrimage”), is a call to all Indians to unite irrespective of barriers like race, class and religion. The plea in the last four lines is worth noting—

Make haste and come to Mother’s coronation, the vessel auspicious

Is yet to be filled

With sacred water sanctified by the touch of all

By the shore of the sea of Bharat’s Great Humanity!

But Tagore saw India’s jumping on the bandwagon of nationalism, a Western construct, as a compromise of all that its rich culture and heritage stood for. As is evident from his own definition of a “nation”, which he saw as a “political and economic union” that brings together people “with mechanical purpose”, Tagore was not willing to attach ethnic, cultural or linguistic attributes to such a community. The choice of lexis indicates his staunch belief that the “mechanical”, manifest in science, commercial and military competition, and the regulatory processes at work would only create an artificial, modern “nation-state” devoid of the most significant facet—the people’s will to unite. He wrote emphatically, “India is no beggar of the West.” Tagore’s alter ego in “The Home and The World”, Nikhil says, “I am willing to serve my country; but my worship I reserve for Right which is far greater than country. To worship my country as a god is to bring curse upon it.” In other words, Tagore was undoubtedly patriotic, but not to the extent where pride in India began to matter more than truth and conscience. This brand of radical hyper-nationalism, according to Tagore, bordered on self-aggrandizement and bred a recipe for disaster.

It is interesting to note the “contrast concepts” that Tagore evolves in order to hint at alternative frameworks to the “nation” within which people’s aspirations can find voice. The first of these concepts is the “society”, which he construes to be an arena for the “self-expression of the social being”. The society, unlike the nation, is a space where the individual naturally identifies with the other members of the community. It has “no ulterior purpose”, and is “an end in itself”. There is nothing forced or artificial about living in such a gathering. The second of these concepts, inherently more evil and malevolent than civil society, is “politics”. This, according to him, encourages greed and selfishness that, in the garb of nationhood, pass off as the moral duty of the people. It is not as though he holds human agency as innocent or devoid of all negativity; but Tagore does view the nation as a catalyst that gives more concrete shape to the selfish and competitive spirit of man.

There is an internal contradiction in Tagore’s theory. While he visualizes self-sacrifice for the sake of the nation as a demoralizing and dehumanizing force since nationalism teaches that “the nation is greater than the people”, on the other hand he also claims that “power of self-sacrifice” and the “moral faculty of sympathy and co-operation” constitute “the guiding spirit of social vitality”. While some scholars have rebuked his theory on the grounds that his own convictions were conflicting, others have pointed out that Tagore always clarified why he saw self-sacrifice as a moral act being different from, and indeed opposed to, sacrifice for the nation. He saw the nobility of sacrifice as being compounded by a moral, universal outlook that is not restricted to the narrow paradigm of the nation. It is his insistent universalism, in a sense, that forms the basis of his critique of modern nationalism.

Intriguingly, Tagore pitted the “inner ideals” of the people against the external forces that the nation superimposes on them. He then synonymized nationalism for professionalism, which he viewed as “the region where men specialize their knowledge and organize their power, where they mercilessly elbow each other in their struggle”. This ruthless competitiveness stood against his belief in universal love. According to Kalyan Sen Gupta, the latter became a core philosophy guiding Tagore’s views on not just nationalism, but on other subjects as well. It might have emanated, Sen Gupta surmises, from Tagore’s understanding of the Upanishads, where the concept of brahman is evoked to represent a universal “world soul” that Tagore interpreted as the “Infinite Personality”. The idea of oneness that accompanies this notion germinates, for him, from experience and not from mere rational deduction. Rather than nationalism, which Tagore saw as being essentially a strategy of antagonism, he insisted on an ontology of love that was inherent in the “personal man”. Implicit in this theory was his understanding of the Manichean opposition between the Real and the Ideal. A progression towards the Ideal, in his terms, was only possible through perfect alienation or absolute detachment from maya, or the world of illusion. On this basis, Michael Collins argues that Tagore’s view of nationalism is “systematically linked to central elements of Tagore’s philosophy that owe nothing of any substance to external or derivative intellectual or philosophical trends.”

Gangeya Mukherji has attempted to study Tagore’s understanding of nationalism in the context of the Austrian philosopher Friedrich Waismann’s theory of linguistic open textures, which states that it is possible for any conceptualization to be inadequately defined, and consequently different people may evolve alternative definitions. This does not indicate, however, that the concept is nebulous or ambiguous; varied definitions may apply in distinct circumstances. For Mukherji, nationalism is just such a concept that has been molded and remolded through history. Tagore always maintained that nationalism is a “great menace”, and that he was not “against one nation in particular, but against the general idea of all nations”. But this did not imply that he was devoid of all attachment to his homeland. His opposition to nationalism was really based on it being an concept imported from the West; he himself stated, “our only intimate experience of the nation is the British nation”. For Tagore, nationalism as seen within the narrow contours of political freedom was undesirable and puerile; instead, he believed in the higher, more worthy sense of “dharma”. He rejected India’s cultural isolation, but simultaneously advocated a deeper appreciation of its traditions. In this sense, according to Amartya Sen, he had a dual attitude to nationalism that is evident is Tagore’s own statement, “Neither the colorless vagueness of cosmopolitanism, nor the fierce self-idolatry of nation-worship, is the goal of human history”.

Surveying Tagore’s take on the Indian national movement in a historical perspective helps shed more light on the subject. He was born in 1861, a mere four years after the rebellion that had inflamed the nation and had challenged, for the first time in very definitive terms, British authority in India. He also lived through the birth of the Indian National Congress in 1885. But it was not until the Swadeshi Movement in Bengal twenty years later that he expressed his political inclinations. The movement began as a reactionary protest to the British partitioning of Bengal in 1905. Over the next two years, Tagore gave lectures and composed patriotic songs that are today counted among his finest pieces of literary prose and poetry. Ezra Pound, a contemporary American poet, quipped, “Tagore has sung Bengal into a nation.”

But this ardent support for the movement did not hold out long; Tagore realized that many were protesting due to sectarian reasons, while others opposed it and were in favor of the partition, also for religious causes. Many Bengali Muslims, for instance, irrespective of their participation in the Swadeshi boycott, were already crowding in Dhaka, which they saw as the Muslim capital of Bengal. At the core of Tagore’s ideas was non-violence. In 1906-07, many areas the mobs in Bengal had taken to raiding British stores and engaging in wreckage. Khudiram Bose’s bomb explosion in 1908, that killed many innocent civilians, was the last straw for Tagore. He withdrew support of the movement, despite cries of betrayal from the nationalists, and never again endorsed or encouraged any political struggle that showed the slightest hint of violence.

III

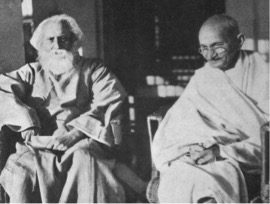

This brings us to a discussion of the intriguing relationship between two of India’s most devoted sons: Tagore and Gandhi. The link between them was established through a common friend, the erudite missionary and social reformer Charles Freer Andrews. Andrews was a resident of Shantiniketan, and went to Durban in 1913 to meet Gandhi, from where he would mention the latter frequently in his letters to Tagore back in Calcutta. In 1915, among the first tasks that Gandhi, a homecoming lawyer, took on himself was to go to Shantiniketan. The two met in March 1915, barely a month after Gandhi’s return from South Africa. This first meeting set the tone for the many occasions on which they met over the next 25 years. They had great respect for each other, and it was this more than anything else that prevented their political differences from marring their personal relationship. Indeed, it was Tagore who gave the title “Mahatma” (the great soul) to Gandhi, and in return Gandhi dubbed Tagore “Gurudev” (the venerable teacher), hailing him as the “poet of the world.” Romain Rolland once described a meeting between Tagore and Gandhi as one between “a philosopher and an apostle, a St. Paul and a Plato.”

The Mahatma and the Poet

(Source: Cover Photograph of Sabyasachi Bhattacharya’s book with the same title)

It is interesting to note that initially, Tagore saw the Rowlatt Satyagraha as Gandhi’s “noble work”. But he refused to support it since he viewed it as essentially an attempt to wrestle some power from the British government, and power for him was inherently immoral and irrational. Gandhi and Tagore’s voices were in unison, however, over the Jallianwala Bagh Massacre the same month (April 1919). Both unequivocally condemned the incident, and Tagore famously gave up his knighthood. But the violence also marked the tacit failure of Gandhi’s satyagraha, as Gandhi himself admitted in his letter dated 19th April 1919: “I at least should have foreseen some of the consequences, specially in view of the gravest warnings that were given to me by friends whose advice I have always sought and valued.” But the end of the Rowlatt agitation did not mean Gandhi’s admission of defeat; on the contrary, he approached the idea of non-cooperation with renewed vigor and the result was the launching of the first national mass movement the next year. Tagore responded to this in his 3 letters to Andrews, published in The Modern Review. Here, he dismissed Gandhi’s idea of swaraj as maya, and questioned the practices of boycott and sabotage on moral grounds.

In the case of both Gandhi’s satyagrahis and the revolutionary firebrands, Tagore refused to lend support, since they resorted to arms and used tools of an incendiary nature to achieve their goals. For them, according to Tagore, it seemed not to matter that ordinary people’s lives were disrupted and, in many instances, uprooted. Ahimsa, one of the two principles that Gandhi stood for, had been embraced by Tagore long before Gandhi appeared on the scene. But Tagore disapproved of non-cooperation and civil disobedience, which Gandhi deployed as tactics in order to mobilize masses and lead national movements. As Tagore wrote in one of his letters to Andrews, “I refuse to waste my manhood in lighting the fire of anger and spreading it from house to house.” It is quite ironic that Tagore did not identify with the ideology of movements guided by the Gandhian notion of non-violence, on grounds of the alleged use of violence.

The difference in their outlooks was especially marked in their disagreement over the road ahead for India. Gandhi, as is well known, espoused political freedom and self-governance as the immediate aim for India. Tagore, however saw the bigger goal as being “steady purposeful education” that would help uplift the Indian masses. Tagore did not sense the need for a “blind revolution” to overthrow colonial rule and gain independence. What he emphasized more was finding solutions to the socio-cultural problems that India was faced with. He believed that the eradication of social evils was only possible through the dissemination of education that would help bring modernization to alleviate the poor, and cultivate freedom of thought and imagination. This was his aim behind the founding of Shantiniketan, a school cum international university where lessons were taught in the open air, harmony with nature was realistically practiced, and education of girls was actively undertaken. The aim of the institution, as Tagore himself expressed in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Stockholm in 1913, was to “make it living and representative of the undivided humanity of the world”. An alternative that was a polar opposite to the prevalent system of education was thus offered. Tagore also set up a centre for rural reconstruction in West Bengal.

In terms of the recognition of India’s backwardness, according to Tagore, the most pressing issue was the caste system. He and Gandhi, though both agreed on it being a social evil, differed in their interpretation of it. For Gandhi, there was a marked difference between varna and caste. He saw the first of these as acceptable and even desirable, since it was “the best form of insurance for happiness and for religious pursuit” (Gandhi in his book, “My Varnashrama Dharma”). Caste, according to him, was a corruption of this tradition that helped organize society and helped conserve social virtues. Tagore disagreed strongly, since he felt caste and varna were both responsible for retarding social progress and restricting human freedom. It demeaned human agency and the application of the mind by reducing them to machines and preventing economic mobility. It aided, and was perpetuated by, illiteracy, poverty, and a limited scope of thought.

Tagore particularly criticized Gandhi for popularizing the charkha (or spinning wheel) as the symbol of liberation and autonomy for India. Gandhi had picked on this machine since it was a metaphor for the dignity of labor that stood for technological innovation, employment generation, and a subtle but visible means of identifying with the impoverished masses. But Tagore noted numerous loopholes in this Gandhian strategy. For one, it simplified and indeed denigrated India’s diversity by applying a homogeneous solution to all its problems. By coercing everyone to take to spinning on the charkha, Tagore felt Gandhi was curbing human talent and regimenting in an almost military fashion. Most importantly, Tagore felt the real problem with the charka was that it was in essence an attempt to regulate and stunt the “truth” that stems from unrestricted creative thought. In this sense, Tagore felt the charkha inhibited rather than foregrounded the human capacity for freedom.

One cannot deny that both Gandhi and Tagore agreed on freedom as being the ultimate aim for India. However, for Tagore, Gandhi’s conception of swaraj in a political dimension diminished its worth and reduced its chance of achieving real success as measured in terms of assuring permanent peace. By adopting politicized forms of nationalism as the means by which it would achieve this end, Gandhi was attributing negative connotations to satyagraha, even hatred in some cases. This, according to Tagore, “would naturally bring out violent and dark forces” (Collins). Instead, Tagore believed that freedom lies within the soul. Most of all, he stressed on the unleashing of the “creative impulse” that would be the sole means of expressing human freedom and liberation.

Unlike what the three Gandhian movements, especially the last of these, aimed at achieving, Tagore did not think it necessary or even desirable to drive the British out of India. One of his greatest ambitions was the coalescence of the two peoples in a manner that did not give in to the divisive tactics aiming to keep them apart on nationalist grounds. He believed that India had many valuable lessons to learn from Britain, and vice-versa. Based on this, many critics have insinuated that Tagore was pro-West and was not in favor of Indian independence. Indeed, one biographer has gone so far as to assert, “Tagore loved his country and his people, but made no secret of the fact that he admired the British character more than the Indian. [For] this, his compatriots never forgave him. For this history will honor him.” On the other hand, scholars like Nirad Chaudhari believe that Tagore had a more personal motive in wanting maintenance of cordial relations with the West post-Independence— that he sought from the West the kind of recognition he was never likely to receive in India.

These accusations take us away from the reality behind Tagore’s beliefs. Perhaps among the foremost reasons for stressing on Tagore’s intellectual debts to the West is the extent to which he interacted with Western intellectuals, both in the course of his travels to the West as well as through his regular epistolary correspondences with them. Harish Trivedi points out that his sense of internationalism stemmed from his anglicized upbringing. He was “dazzled” by European literature in particular, and always claimed that he was familiar with not one nation, but two: his own, and England. The receipt of the Nobel Prize only strengthened his ties with people from other countries, many of whom came to visit him in Shantiniketan. In truth, Tagore felt India would make a mistake in dissociating itself from the rest of the world, since a lack of engagement with other countries would make it insular. This would amount to an appropriation of a brand of “provincial nationalism” that would tend to isolate India and make diplomatic foreign relations impossible to achieve.

And yet, we know beyond the shadow of a doubt that Tagore epitomized Indian heritage (he was, after all, the same man who composed what went on to become India’s national anthem). In this sense no one could have been more against cultural westernization than him. As Michael Collins writes, “in contradistinction to those who have accentuated a ‘derivative’ element of Tagore’s thinking, Tagore’s philosophical critique of nationalism was firmly grounded, above all else, in a critical reading of Indian traditions, particularly in evidence in Tagore’s deployment of his Brahmo inheritance and the ideas of the Upanishads.”

Hence, the liberal humanism of Tagore underlined his conceptualization of nationalism. He was an idealist par excellence whose global vision encompassed people of all races. This conviction foregrounded his rejection of the notion of the concept of “nationhood” prevalent in the West. As is evident from his poems in the “Gitanjali” and his tract on “Nationalism”, a pervading sense of world unity was more important than the promulgation of parochial interests. India, for Tagore, was a distinct civilization with a society seeped in historical tradition that must not attempt to imitate the parameters set by the West. It must not lose sight of the gargantuan task before it—coming to terms with its diversity and its multi-ethnic character. This, along with spiritual upliftment, socio-economic progress especially through education, and morality, were worthier causes than sacrificing one’s life for one’s homeland. Even Gandhi, whose several divergences from Tagore’s thoughts have been noted above, agreed at a very basic level with his precepts. Both espoused the sagacious philosophy of oneness and harmonious coexistence that, irrespective of national interests, must embrace all forms of humanity.

Therefore, when Gandhi wrote the following in 1940, he was echoing a nation’s sentiment: “In the death of Rabindranath Tagore, we have not only lost the greatest poet of the age, but an ardent nationalist who was also a humanitarian.”

References

Collins, Michael. “Rabindranath Tagore and Nationalism: An Interpretation” in University of Heidelberg Papers in South Asia and Comparative Politics, 2008

Mukherji, Gangeya. “Open Texture of Nationalism: Tagore as Nationalist” in Rupkatha Journal on Interdisciplinary Studies in Humanities, Vol. 2 No. 4, 2010

Sinclair, May. “The Gitanjali: Or Song-Offerings of Rabindra Nath Tagore” in The North American Review, Vol. 197 No. 69, May 1913. pp. 659-676

Tagore, Rabindranath. Nationalism, Macmillan and Co. Limited, St. Martin’s Street, London, 1918

–. “Gitanjali” (Song Offerings), Macmillan and Co. Limited, St. Martin’s Street, London, 1913

Trivedi, Harish. “Nationalism, Internationalism and Imperialism: Tagore on England and the West” in G. R. Taneja and Vinod Sena (eds.), Literature East and West: Essays Presented to R. K. Dasgupta, Allied Publishers, New Delhi, 1995. pp. 163-176

Quayum, Mohammad A. Imagining ‘One World’: Rabindranath Tagore’s Critique of Nationalism, International Islamic University Malaysia, 2004

Yeats, W. B. Introduction to “Gitanjali”, September 1912

Anurag Advani (MAPH ’15) is a 2014 Tata Scholar. He graduated in History from St. Stephen’s College, University of Delhi in May 2014. His interest is piqued by a range of subjects, among which are world (particularly medieval Indian) history, fiction, rendering theatrical performances, and the study of gender identities. In addition, he likes to read and listen to poetry, and some of his poems have been published.