Holmes’s Companions: Refiguring Watson as a Woman

ESSAY by Malcah Effron

The relationship between Sherlock Holmes and John Watson has provided a standard basis for detective narrative for over century, establishing tropes that identify different patterns and critical modes in crime fiction. For instance, in his rules for writing detective stories, Ronald Knox uses Holmes and Watson to explain his ninth rule: “The stupid friend of the detective, the Watson, must not conceal any thoughts which pass through his mind” (xiv; original emphasis). Since the popularity of the Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s series, many detective narratives—written filmic, and televisual—have built upon this detective and narrating sidekick trope, exploring the partnership relationship in the detective form. Several have explored this concept by explicitly adapting the Sherlock Holmes canon, writing more stories, such as Adrian Conan Doyle and John Dickson Carr’s The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes (1952) and Caleb Carr’s The Italian Secretary (2006), or re-imagining and re-interpreting the original stories, such as Billy Wilder’s The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes (1970) and the BBC’s Sherlock (2010- ). Most frequently, these series maintain the standard image of the Watson figure as Knox describes him: “if he does exist, he exists for the purpose of letting the reader have a sparring partner, as it were, against whom he [the reader] can pit his brains” (xiv; my emphasis). In other words, the Watson figure is the inferior intellect with whom the reader can successfully match wits. In many of these instances, Watson is rewritten in a variety of capacities, but predominantly as a male.

While the dominant method of imagining Watson maintains Holmes’s single-sex pairing, some twentieth and twenty-first century authors have re-imagined Watson, or at least the Watson-figure, as a woman. These versions of the female Watson reveal popular assumptions about the roles of women in the contemporary eras of the texts. Notably, in the post-feminist era,[1] to define Watson as a woman, these authors have also re-interpreted the relationship between Holmes and Watson, moving beyond the relationship of flatmates and companions into a situation that challenges Knox’s correlation of the figure of Watson and the trope of the “stupid friend.” The female Watson interpretations and representations vary in character and authority, revealing shifting attitudes toward women and femininity from Rex Stout’s “Watson is a Woman” to CBS’s Elementary (2012- ) based on the so-called sidekicks’ respective positions to Sherlock Holmes. These shifting opinions lead to shifting responses to the role of the detective sidekick in the crime genre.

Historically, the exploration of Watson as a woman begins in a parallel manner to the breadth of interest in the Holmes-Watson dyad as a homosexual couple, namely with an interest in the sexual lives of Holmes and Watson—an area Conan Doyle rarely, if ever, narrates. The first recorded interpretation of Watson as a woman appears in detective novelist Rex Stout’s 1941 speech to the New York-based Sherlock Holmes fan group, The Baker Street Irregulars. This group of devotees of Conan Doyle’s stories—referred to by the group as the Sacred Writings—scoured (and still scours) the narratives to understand fully the biographies, methods, and adventures of the characters, treating Holmes and Watson as entities with lives beyond their textual confines and Holmes as the ultimate incarnation of detective and deductive prowess. These debates occurred over minutiae such as the textual validity of Dr. John Watson’s second marriage. In a novel take on the issue, Rex Stout, group member and author of the detective-and-narrating sidekick Nero Wolfe series, made the shocking claim that the debate over Watson’s second marriage is absurd because Dr. John Watson is, in fact, Mrs. Sherlock Holmes, née Irene Watson, presented in the so-called Sacred Writings as Irene Adler. While Stout’s speech uses close reading rather than narrative extension and reimagination—the strategies employed by the other texts considered in this article—his suggestion highlights his contemporaries’ mainstream attitudes toward the place of woman and the role of wife in the 1940s, assumptions the narrative reinterpretations seek to undermine at the turn of the twenty-first century.

Stout identifies Watson as a female because “the Watson person, describes over and over again, in detail, all the other minutia [sic] of that famous household—suppers, breakfasts, arrangement of furniture, rainy evenings at home.” He highlights that Watson cares about these domestic minutiae, whereas Holmes does not, and, Stout proposes, caring about such things falls under the responsibility and, more importantly, the interest of women, calling into question Watson’s pretensions at being a male companion. He also doubts Watson’s maleness because the sidekick “‘endeavor[s] to break through [Holmes’s] reticence.” And he doubly faults Watson for failing “to employ one of the stock euphemisms such as, ‘I wanted to understand him better,’ or, ‘I wanted to share things with him.’” Failing to reward Watson for candor while accusing other women of deception, Stout here suggests that only women are interested in understanding people—or at least their male partners— more fully, rather than accepting outer stoicism as an appropriate way of interacting with others. In sum, women are nosy individuals who care about minutiae rather than items of larger importance.

These so-called womanly interests are not Stout’s only clues to the Holmes-Watson marital status. Stout claims “[a] man does not munch silently at his toast when breakfasting with his mistress; or, if he does, it won’t be long until he gets a new one. But Holmes stuck to her—or she to him—for over a quarter of a century”—indicating a nuptial tie. By providing further examples of what he calls “painful banality,” Stout argues that Dr. Watson is, in fact, Mrs. Sherlock Holmes. Through further anagrammatic gymnastics applied through cryptographic interpretations of Conan Doyle’s short story titles, Stout the woman presented as Irene Adler, thus tying all elements together nicely. As such, Stout exposes the domestic companions as a heterosexual domestic couple.

Though Stout identifies Mrs. Holmes as “the woman” (“Scandal in Bohemia”), he gives the female Watson no credit for anything other than these standard so-called feminine foibles. When contemplating the evidence of the Holmes-Watson domestic arrangement, he bemoans “Sherlock Holmes was not a god, but human–human by his suffering” at the hands of a wife. As a married man, Holmes loses his deified place—no longer exclusively a man of deduction and reasoning, but one whose emotions—or other non-rational inclinations—have trapped him in what Stout presents as the plight of man—matrimony. Stout describes the marriage as so oppressive that Holmes feels compelled to use Reichenbach Falls to escape from the marriage. He reads Watson’s account of Holmes’s return as “gibberish, below the level even of a village half-wit” because the narrative presents woman trying to cover her shame at being abandoned rather than an account of the events as they occurred.

These attitudes or readings are not at odds with the notion of Watson as the inferior mind in the investigative duo. However, by identifying Watson as Irene Adler, and then declaring the story “below the level even of a village half-wit,” he undermines the place of Adler in the Holmes canon, as Holmes is bested by sexual urges rather than intellectual wits. Watson/Adler’s diminished status reinforces the Holmes’s misogynistic assumption of women’s inferior ratiocinative—and thus intellectual—capacity. Stout argues that Watson is a woman exclusively because of the inferiority and domesticity of the character, reaffirming an attitude that disparages women, their intelligence, and their role in society.

Novelistic reinterpretations of Watson as a woman have not, however, accepted Stout’s misogynistic tone, but rather tend toward feminist rewritings. Fred Erisman explores three series since the 1990s that have deliberately rewritten the Holmes-Watson relationship to examine the roles of women, noting that “[b]y replacing the Watsonian voice with that of a woman, [these series] challenge the conventions of historical Victorian England and the classic detective story […] encourag[ing] readers to test the realities and social currents of this century against the fictional representations of those of the preceding century” (186). Erisman looks at novels that approach the Holmes narratives from multiple perspectives: Mrs. Hudson’s in Sydney Hosier’s series; Irene Adler and her female companion, Penelope “Nell” Huxleigh, in Caroline Nelson Douglas’s series, and Mary Russell in Laurie R. King’s series. Of these series, King’s is the only one that directly replaces the traditional Watson role of narrator-cum-investigative partner with a woman. In the Hosier series, Mrs. Hudson continues to occupy the landlady-servateuse position in the household, despite her added influence in the investigations. In the Douglas series, Irene Adler is positioned from the opposite side of the Holmes-Watson spectrum, as she is the primary investigator who has a female companion, not Holmes’s narrator-cum-investigative partner. King, however, writes a continuation of the Holmes canon, picking up after the consulting detective has retired to Sussex to raise bees.

However, Mary Russell, as companion, cannot easily be reinterpreted by the limited view of femininity that allowed Stout to “expose” Dr. Watson. King, as Megan Hoffman argues, “undermines the myth of Holmesian masculine rationality” (81; my emphasis). Countering generations of critics who use Watson to exemplify the bumbling sidekick of inferior intelligence, Russell actively sets herself up as Holmes’s intellectual equal from the beginning of the first novel: “I do know that I have never, in a my travels, met a mind like Holmes’. Nor has he, he says, met my equal” (Beekeeper 28). While she does recognize an initially inferior position, referring to herself repeatedly as a “yapping dog” (7), the goal of the series, as it develops, is to establish an equal, female partner for the superlative—as the Baker Street Irregulars would argue—Sherlock Holmes. By the end of the first novel, Russell has attained this status: “There was no hesitation left. He had let go all doubt, and was telling me in crystal clear terms that he was prepared to treat me as his complete, full, and unequivocal equal” (259). This acknowledgment of her equal status firmly establishes Russell as a protagonist—if not the protagonist—of her series. She is not the bumbling narrator-sidekick, but an “unequivocal equal” partner in the detective operation. As such, the Mary Russell figure rewrites Watson not only as a woman, but as a detective protagonist.

As partner and narrator, Russell figures more prominently in the narratives than Conan Doyle’s Watson ever does. She has her own exploits and recounts them as fully as those of Holmes, as when she is given her own case to investigate in The Beekeeper’s Apprentice: “that one case stands out in my mind, for the simple reason that it marked the first time Holmes had granted me free rein to make decisions and take action” (89). Dr. John Watson never assumes such positions of responsibility, even in The Hound of the Baskervilles, when Holmes ostensibly sends Watson to Dartmoor to protect their client and make onsite observations. In Conan Doyle’s novella, Watson’s autonomity is circumvented because Holmes also goes to Dartmoor, as is revealed in the last third of the narrativ (Doyle 359-60). Moreover, the Russell novels also narrate how Russell takes action, such as when she rescues the kidnapped heiress in The Beekeeper’s Apprentice (130-34) or when she participates in the majority of the action in A Monstrous Regiment of Women (1995),[2] as most of the story narrates her attendance at women’s meetings and her exploits in uncovering the criminal activity within these progressive societies. In this regard, Russell becomes as much as a protagonist as, if not more than, Holmes, modifying the trope from detective-cum-narrating sidekick to detective duo.

Megan Hoffman identifies this importance, emphasizing the gendered aspect of King’s revision: “Russell […] recognizes herself not only as Holmes’s equal but as a woman who is Holmes’s equal” (91; original emphasis). The series thus counters the misogynistic attitude of Sherlock Holmes already well established in detective fiction scholarship, such as is noted in the works of Stephen Knight and Robert S. Paul and as is manifested responses like Rex Stout’s speech. Because King sets her stories during Holmes’s retirement, this perhaps shows the detective humanizing with age. However, the series as a whole is more invested in character development than Arthur Conan Doyle’s (much) shorter narratives, so these humanizing aspects can appear more fully in King’s series than in what Stout refers to as the Sacred Writings. The fuller character development supports Erisman’s argument about how the female narrators allow the series to challenge the classic detective story—or at least the classical critical assessments of the detective story to which Erisman’s article responds—by moving away from the plot-driven focus of the originals to a character-driven focus of the Russell addenda. This humanizing aspect does, however, somewhat strengthen Stout’s notion that women “want to understand [people] better.”

The Russell series also follows Stout’s reading in the sense that Mary Russell marries Sherlock Holmes in the second novel. Despite the three-decade age gap between the characters, the marriage is made one of equals because of their similar intellect, exchanging physical for mental compatibility. Holmes sees himself echoed in Russell, in her intellect and in her behavior. While working through a situation, Russell interrupts her own comment when she finds Holmes laughing:

“ I don’t know. I suppose I thought that telling it to you might help me clarify it in my own mind. It’s all so—Why are you laughing?”

“At myself, Russell, at a voice from the past.” He chuckled. “I used to say the same thing to Watson.” (King, Monstrous 72)

Recognizing his old habits in Russell, Holmes indicates the equality of their methods, making their partnership—both personal and professional—an equal partnership. Or, if we accept Watson as an inferior, in this instance Holmes situates himself as Russell’s sidekick. In setting up its characters in this format, King’s narrative refigures the gendered positions articulated in Stout’s interpretation of woman and wife, highlighting instead Russell’s position that “women [are] the marginally more rational half of the race” (King, Beekeeper 10).

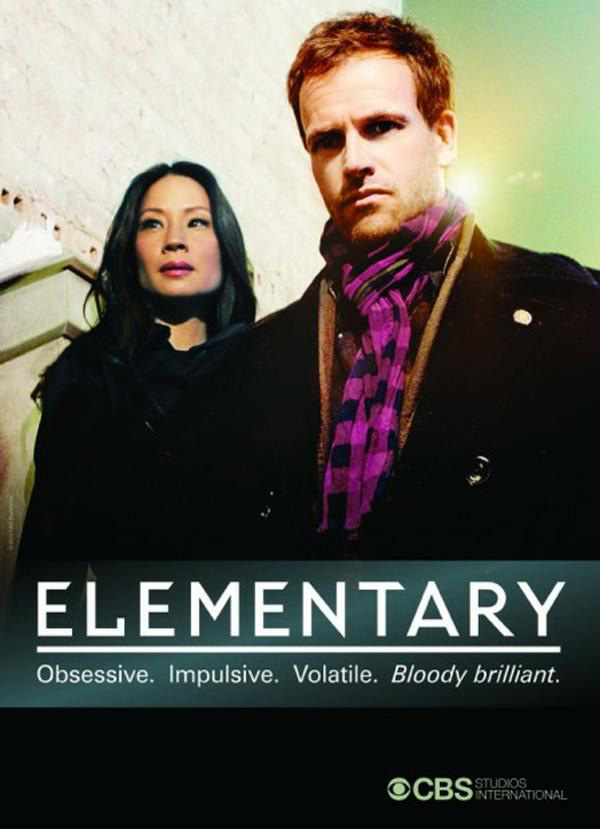

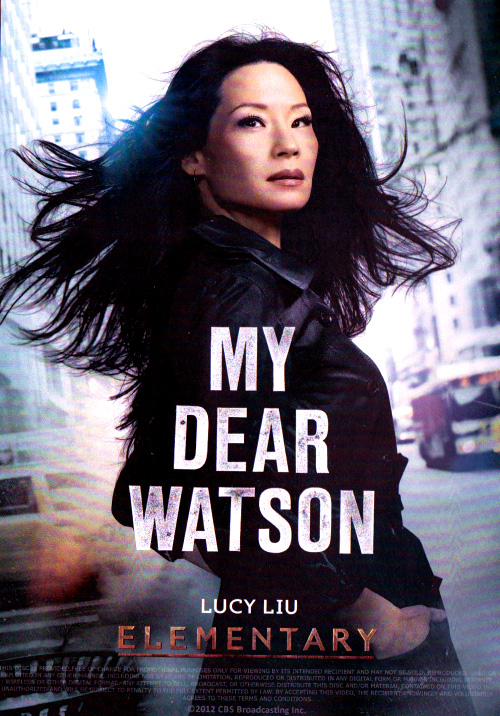

While King’s Holmesian update attempts to maintain the Conan Doyle style—even presenting the novels as derived from the diaries of the narrator, as Conan Doyle does in A Study in Scarlet—some adaptations of the Holmes figure have moved not only into alternate modes but into alternate media. Perhaps intending to capitalize on the success of the BBC’s modern television adaptation Sherlock, the American television network CBS launched Elementary in fall 2012. Set in New York City, this adaptation stars Jonny Lee Miller as a British Sherlock Holmes and Lucy Liu as an Asian-American Dr. Joan Watson. Lucy Liu’s Watson is an independent woman of the twenty-first century. She has a medical doctorate and surgical training; she has a keen sense of fashion; and she lives independently from the desires of her (stereo)typical Asian-American family. These elements of her independence seem to frame her in the King model of a Holmes companion rather than a Conan Doyle or Stout version.

However, her characteristics and her attitude initially set her up as intellectually and physically inferior to Holmes, despite Holmes’s status as a recovering heroin addict. Though she was a surgeon, she repeatedly asserts that she no longer is one, and is now a “sober companion,” or as Holmes often refers to her, “his babysitter.” Though she professes to have been her medical school valedictorian and often contributes information from her medical knowledge, Holmes treats her—and she behaves—as a less observant and less critical tag-a-long rather than an active partner. Moreover, he frequently comments on her lack of self-defense training and rebukes her for failing to learn self-defense (“Details”). Her inferiority to Holmes is positioned from the beginning of the narrative as, in the pilot, Holmes at one point says to her, “I’m very pleased. Not for myself, but for you. There is some hope for you as an investigator.” While this might be taken to show respect for Watson, it more appropriately shows Holmes’s arrogant refusal to accept that he needs Watson’s help, as he makes this patronizing assertion from inside a jail cell. His praise is belittling, using the phrase “some hope for you” (my emphasis), and he rejects her position as sober companion, instead interpreting her presence as detective-apprentice.

As the series progresses, however, she moves from the role of sober companion to that of detective-apprentice, and Holmes’s appreciation for her grows. In the episode “Details,” in response to Watson’s protestations that she is his sober companion, Holmes transitions Watson from her now-defunct role as sober companion to her new role as detective-apprentice:

HOLMES: I know that you lied to me several weeks ago when you said that my father had renewed your contract. I found out when I telephoned him last week. I am not angry. If anything, I am grateful. You saw that I was in a raw state, and you stayed to see me through it. But when I learned that that was a lie, however, I deliberately adopted a more sanguine mode. I wanted you to see that I was well again so that you could move on. But the most curious thing happened. You stayed. Days passed, and a week. It became clearer and clearer that you were not staying for me, but for yourself.

WATSON: Sherlock, I…

HOLMES: It’s difficult for you to say aloud, I know. So, I won’t ask you to. Rather, I would ask you to consider a proposal. Stay on permanently. Not as my sober companion, but as my companion. Allow me to continue to teach you. Assist me in my investigations.

Holmes openly states that he appreciates Watson’s dedication to her work as a sober companion and thus as his friend, and this progression in the series shows Holmes’s humanization resulting from Watson’s influence. However, though Holmes acknowledges and thus appreciates Watson’s successful work as sober companion, she remains, until the season finale, in the inferior position of apprentice. While the new relationship Holmes proposes is that of companion, a term which might suggest equality, the verbs he uses to describe the relationship—“teach you,” “be my assistant”— reaffirm the master-apprentice positioning. The continual camera cuts back to Watson’s subdued and pensive face during Holmes’s offer intensify this teacher-trainee relationship. Additionally, as Holmes follows the offer with a discussion of salary and other financial arrangements, the relationship repositions Watson as dependent on Holmes rather than independently contracted to him. Thus, despite CBS’s seemingly progressive move of refiguring Watson as female, the majority of the first season remakes a surgeon into a caregiver, albeit in a non-traditional format, and then remakes the self-employed caregiver into an employee. Elementary thus does not present as dramatically progressive a female Watson as the King series.

Though Elementary diminishes the female Watson’s relative position to Sherlock Holmes in comparison to the King series in her role as employee and as student, the Holmes-Watson partnership in the American television series does not fall into the love-plot patterns of other interpretations of the Holmes-Watson relationship, whether heterosexual or homosexual.[3] Stout’s interpretation of Watson as wife necessarily reinterprets the close relationship between Holmes and Watson as sexual rather than platonic. While, as discussed previously, the Russell series develops a marriage of equals between Sherlock Holmes and Mary Russell, King’s novels still rather quickly fall into the pattern of close relationships, and particularly close relationships between the sexes, as necessarily sexualized. The first novel of the series begins by working against this premise, calling attention to assumptions about relationships between men and women for the explicit purposes of refuting them. The novel’s supporting characters presume all heterosocial pairings to be sexual, so the companionship of an older man and a young woman is inherently perceived to be perverse. Russell’s aunt invokes this attitude when she threatens to end their friendship by “stir[ring] up talk and rumours in the community” (King, Beekeeper’s Apprentice 26). Holmes’s police colleagues also insinuate that the relationship is not strictly platonic and professional, only to be cowed by Holmes:

“She…introduced herself. As your ‘assistant.’ I ask you, Mr. Holmes, is this truly necessary?”

There were multiple layers insinuated into his question but, innocent that I was, I did not immediately read them…until I saw the way Holmes was just looking at the man, and suddenly I felt myself flush scarlet head to toe…

“Miss Russell is my assistant, Chief Inspector. On this case as on others.” That was all he said, but Connor sat back in his chair, cleared his throat, and shot me a brief glance that was all the apology I would have, considering that nothing had actually been said aloud. (King, Monstrous Regiment 103)

In this sublingual exchange, the Chief Inspector expresses his doubts that a relationship between an older man and a young woman can be as innocent as Russell’s initial reaction clearly acknowledges it is. Holmes reinforces the non-sexual nature of their relationship in the first novel, clearly putting the official detective in his place without needing to say anything more explicit than the detective does himself. These initial moments in the series seem in keeping with the rhetoric firmly developed in relation the equal partnership between Holmes and his new Watson-figure.

This initial set-up, however, makes the reversion to a love-plot between Holmes and the Watson-figure weigh differently in terms of the progressive and feminist positioning of the series. Given the extensive work King does to deny a romantic relationship between Holmes and Russell in her first novel, the introduction of a marriage plot at the start of the second reads as rescinding the principles highlighted in the first. While King’s move might have been structurally motivated for the sake of a continuing series—if her characters are married, she can stop defending the continued unsupervised liaison between a young woman and an older man—the introduction of the marriage plot validates the Chief Inspector’s presumptions in the first novel. Holmes and Russell might not have been lovers at the start of their relationship, but even if theirs is a marriage of equals, the Mary Russell series does not ultimately support claims that men and women can sustain a wholly platonic friendship.

Though CBS’s Elementary does not allow for the potential of a marriage of equals because it, as discussed previously, does not establish equality between Sherlock Holmes and Joan Watson, it does not succumb to the pressures of sexualizing the male-female partnership in the narrative. Though the series does not develop a love-plot, like King’s The Beekeeper’s Apprentice, the series does invoke the sexual tensions presumed to exist between the pairing of an attractive man with an attractive woman. In particular, Elementary calls attention to this motif as a cinematic and televisual trope, as the series introduces the question of “will they or won’t they” in the first five minutes of the pilot. Watson’s first introduction to Sherlock Holmes is staring at his naked back through a window in his brownstone, and Holmes’s first words to Watson are “Do you believe in love at first sight? I have never loved anyone as I do you right now in this moment.” Seconds later Holmes reveals that he is quoting from one of the several televisions he uses to train his observation skills, but the cut to the shocked look on Watson’s face indicates that this initial moment suggests the possibility of a future romantic relationship that does not appear in the other series—despite the marriage in King’s series.

This tension becomes important in the resolution of the first season finale, which ends in the successful arrest of Moriarty based on a tip from Watson, thus giving the title a delightful double entendre in its name “Heroine.” Watson succeeds because she realizes that Moriarty, revealed as the resurrected Irene Adler, is still in love with Holmes. Watson learns this when forced to have lunch with Adler/Moriarty, a lunch that takes the form of an ex-lover evaluating her former partner’s new love:

ADLER/MORIARTY: You’re not afraid of me.

WATSON: I’m too angry to be afraid. Or maybe it’s just because we’re in a crowded restaurant.

ADLER/MORIARTY: Over the course of my career I’ve plotted exactly seven murders that were carried out in crowded restaurants. Killing you here is far from impossible. It’s just not what I want.

WATSON: Why am I here?

ADLER/MORIARTY: Because he took an interest in you. I’d like to understand why.

WATSON: Because you find him so fascinating. What was the word that you used the other day? … A work of art.

ADLER/MORIARTY: As far as I can determine, you’re sort of …a mascot. You were his sober companion, a professional angel to perch on his shoulder to fend off his many demons. But now, now I don’t know what you are…Do you want to sleep with him?

WATSON: I thought you told him that you were just like him…and saw the same things that he did.

ADLER/MORIARTY: Well, women can be a little bit more difficult to read. Just ask Sherlock.

WATSON: Hmpf.

The catty exchange highlights the former lover’s attempt to disparage the new woman’s sense of security and importance in the man’s life, using terms and phrases like “mascot,” “professional angel,” and “I don’t know what you are.” Moreover, Adler/Moriarty explicitly introduces the idea that Watson’s relationship with Holmes must necessarily be sexual because she is a woman working closely with an attractive man, asking her outright if she “want[s] to sleep with him.” Watson reciprocates by similarly asserting her new place in Holmes’s life by challenging the former lover’s confidence in her knowledge of her ex, questioning Adler/Moriarty’s claims that she is just like Holmes. This jealous interest in the new woman in Holmes’s life allows Watson to see that the Irene Adler element of Moriarty’s personality—the element in love with Sherlock Holmes—is not fully mastered by the master criminal component, and thus she is able to arrange a solution in the season finale that successfully captures the series’s criminal.

This tip and strategy finally wins Watson an equal place in Holmes’s esteem, when he acknowledges that Watson, in fact, is the one who outsmarts Moriarty: “You said there was only one person in the world who could surprise you. Turns out there are two.” Though Watson never states her discovery on screen, Holmes clearly identifies Watson’s conclusions when he uses Adler/Moriarty’s words from the lunch against his nemesis: “You know, she solved you. The mascot, Watson. She diagnosed your condition [being in love] earlier this evening.” Holmes reinvigorates Watson’s role in this denouement, by sarcastically rejecting her previously established role as mascot-sidekick and by using the terminology of medical diagnosis, giving credence to Watson’s former profession. This conclusion brings Watson into an equal partnership at the end of the season, although perhaps not the unequivocally equal partnership of Holmes and Russell.

But the series has not shut down the possibility, all while strengthening a sense of equality between Holmes and Watson:

HOLMES: Remember the rare bee I was given for proving that Gerald Lyden had been poisoned?

WATSON: The bee in the box, sure.

HOLMES: Osmia avosetta is its own species, which means it should not be able to reproduce with other bees. And yet, nature is infinitely wily.

WATSON: So box bee got another bee pregnant?

HOLMES: Quite so, which means they should be classified as an entirely new species. The first newborn of which is about to crawl its way into the sunlight…As the discoverer of the new species, the privilege of naming the creatures falls to me. Allow me to introduce you to Euglossa watsonii.

WATSON: You named a bee after me? You named a bee after me!

HOLMES: There should be dozens more within the hour. If you like I can come get you once they’re all here.

WATSON: It’s alright. I think I’ll just watch. (“Heroine”)

By conferring the honor of the bee’s name upon Watson rather than himself, Holmes recognizes Watson’s importance to his accomplishments, both personal and professional. This is the ultimate humbling of the Holmesian narcissistic personality that dominates the first season, as the discoverer relinquishes the standard opportunity to name the bee after himself and instead names it for his companion. While the tenderness of the tone in this final scene of the first season leaves open the question of “will they or won’t they,” this moment can equally be read as a moment of mutual respect, particularly as Watson recognizes the importance of Holmes’s gift and wishes to wait with him rather than leave him by himself. As more overtly a scene of companionship than romance, even with Adler/Moriarty’s question, Elementary does not actively further a romantic plot between Holmes and Watson. In fact, the jealousy underscoring Adler/Moriarty’s pointed question highlights the erroneous nature of this assumption. For this reason, in terms of sexual stereotypes as pertain to sexual relationships, Elementary seems more progressive than the King series,[4] even though King’s series makes the female Watson-figure the protagonist, not Sherlock Holmes.

CBS’s script does not refer to Joan Watson as Holmes’s “complete, full, and unequivocal” (King, Beekeeper 259) partner, as King’s novel does for Mary Russell, but both women similarly triumph over female criminals in their first “novel-length” appearance, if we consider a television season as relatively the same narrative length as a novel. The women’s successes highlight these texts’ ambivalent reclamation of the role of women in the Holmes oeuvre. Both the King and the CBS series reincarnate Moriarty the master criminal as a woman, as Moriarty’s daughter and as Irene Adler, respectively. This presents Moriarty as a true Nemesis of Greek mythological proportions. The female criminal mastermind might seem as feminist a rewriting as the female Watson, except that, as Merja Makinen summarizes, in crime fiction “women characters [blossom] into the more sinisterly dangerous construction of the vamps” (92). The femme fatale is nothing new, and is equally contained at the end of the cases of the female Watsons as at the conclusion of classic hard-boiled narratives. Moreover, these female Watsons triumph over female villains, suggesting knowledge that only one female could identify in another—such as Joan Watson’s jealous ex diagnosis. After all, as Adler/Moriarty states, “women can be a little bit more difficult to read.” However, the texts also can be read as suggestion that, while only women can read women, women might be equally incapable of reading men.

Nevertheless, these series bring the Watson characters from the sniveling wife of Stout’s derogatory analysis to a strong, independent position in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. While they show that certain gender assumptions are in play, these women, in their own rights, become detectives alongside the great Sherlock Holmes, defeating his N/nemesis and proving her skills in reasoning and deduction. Though they might still be(come) wives and lovers, the recent female Watsons are more than doting chroniclers; they are true partners.

The notion of true partners indicates a significant shift to the detective-sidekick pattern established in the Holmes-Watson style private detective series. While the male-female detective partnership appears with greater investigative equality in other detective fiction forms—such as the police procedural—private detective series have frequently evolved in the Holmes-Watson model, such as Rex Stout’s Nero Wolfe series, or have veered toward the lone detective, such as is highlighted in the hard-boiled genre. For the writers creating female Watsons—rather than just reimagining the original Watson as Stout does—the creation of a female counterpart seems to demand of these writers extra attention to the position of the woman in the partnership relationship. Rather than simply using a “sidekick” position to denote a traditionally inferior female role—as Stout does—King and the CBS writers invest the Watson character with more strength and dynamism, in some sense to justify the characters’ transgendered existence. Moreover, these texts actively rewrite the Holmes-Watson dyad because the cultural resonance of Holmes and Watson predicates the assumption of a homosocial pairing. Such major revisions to cultural assumptions about the Watson position enable these writers to make significant changes to the roles of the Watson character. Even in Elementary, where Joan Watson is not initially given the strength of King’s Mary Russell, the economics of the show emphasize the female position, as Liu, rather than Miller, becomes CBS’s means of garnering an audience for a twenty-first century Sherlock Holmes adaptation fighting against the popular appeal of tBenedict Cumberbatch’s a contemporary incarnation of Sherlock Holmes in the BBC’s very popular Sherlock. In this capacity, the female Watson not only allows for reimagining of women in the Sherlock Holmes oeuvre—attributing to them strength and character denied to all but one female in the Sacred Writings—but also a way to move away from generic assumptions that a bumbling sidekick narrator is necessary to hide the thoughts of the detective and thus the excitement of the denouement from the reader. These contemporary female Watsons refigure the role of the detective dyad from detective and sidekick to an equal partnership, so the women Watsons carry not only the role of women in classical detective fiction but also the classical detective form into the twenty-first century.

Notes

[1] By post-feminist, I do not mean to engage with discussions of definitions of feminism but rather to highlight a period of history that exists with knowledge and experience of the feminist movement as opposed to existing prior to it. For a significantly more nuanced discussion of the term and its contemporary critical uses, see Stacy Gillis, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford’s Third Wave Feminism (2007).

[2] Which won a Nero Wolfe award, an award given by the Wolfe Pack, a society that treats Stout’s character the way The Baker Street Irregulars treat Conan Doyle’s.

[3] While the subject is not within the remit of this argument, many critical and creative responses to the Sherlock Holmes series have reimagined the Holmes-Watson relationship as romantic or sexual rather than platonic. In addition to the heterosexual marriages detailed by Stout and King, many authors have explored the idea of a romantic or sexualized relationship between Sherlock Holmes and his male companion, John Watson. For a catalogue of such interpretations, see Drewey Wayne Gunn’s The Gay Male Sleuth in Print and Film: A History and Annotated Bibliography (2012).

[4] However, as CBS has decided to continue Elementary for a second season, this could still change and repeat the standard television tropes of creating a romantic liaison between the male and female leads (cf. CBS’s Nash Bridges (1996-2001), JAG (1995-2005), and CSI: Crime Scene Investigation [2000- ])

Works Cited

Carr, Caleb. The Italian Secretary: A Further Adventure of Sherlock Holmes. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005. Print.

Doyle, Adrian C. and John D. Carr. The Exploits of Sherlock Holmes. 1952. New York: Gramercy Books, 1999. Print.

Doyle, Arthur C. The Hound of the Baskervilles. 1902 The Complete Sherlock Holmes Long Stories. London: Book Club Associates, 1978. 242-405. Print.

Elementary. CBS. Creator Robert Doherty Sept 2012-May 2013. Televsion.

Erisman, Fred. “If Watson Were a Woman: Three (Re)Visions of the Holmesian Ménage.” Clues: A Journal of Detection. 22.2 (2001): 177-88. Print.

Gillis, Stacy, Gillian Howie, and Rebecca Munford. Third Wave Feminism: A Critical Exploration. 2nd ed. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2007. Print.

Gunn, Drewey W. The Gay Male Sleuth in Print and Film: A History and Annotated Bibliography. Lanham: Scarecrow Press, Inc., 2013. Print.

Knox, Ronald. Introduction. Best Detective Stories: First Series. Ed. Ronald Knox. London: Faber and Faber Limited, 1929. vii-xxii. Print.

Hoffman, Megan. “Assuming Identities: Strategies of Drag in Laurie R King’s Mary Russell Series.” Murdering Miss Marple: Essays on Gender and Sexuality in the New Golden Age of Women’s Crime Ficiton. Ed. Julie H. Kim. Jefferson: McFarland & Company, Inc., 2012. Print.

King, Laurie R. The Beekeeper’s Apprentice. New York: Picador, 1994. Print.

—. A Monstrous Regiment of Women. New York: Bantam, 1995. Print.

Knight, Stephen. “The Case of the Great Detective.” Critical Essays on Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Ed. Howard Orel. New York: G. K. Hall & Company, 1992. 55-65. Print.

Makinen, Merja. Feminist Popular Fiction. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2001. Print.

Paul, Robert S. Sherlock Holmes: Detective Fiction, Popular Theology, and Society. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1991. Print.

The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. Dir. Billy Wilder. Perf. Robert Stephens, Colin Blakely, Genviève Page. United Artists Corporation, 1970. Film.

Sherlock. Creators Steven Moffit and Mark Gatiss. BBC One. July 2010-Jan 2012. Television.

Stout, Rex. “Watson Was a Woman.” 1941. Sacrilige! n.p., n.d. Web. 4 June 2013.

Malcah Effron (MAPH ’05) is a lecturer in the English department at Case Western Reserve University. After graduating MAPH, She earned her Ph.D. in English Literature from Newcastle University, England. She edited The Millennial Detective (McFarland, 2011) and has contributed chapters to A Companion to Crime Fiction (Blackwell, 2010) and Constructing Crime (Palgrave, 2012) as well as articles to The Journal of Narrative Theory and Narrative. She is also the co-founder of the international Crime Studies Network (CSN).