The Serpent, Subtle and Brazen: Idolatry, Imagemaking, and the Hebrew Bible

ESSAY by Carina del Valle Schorske

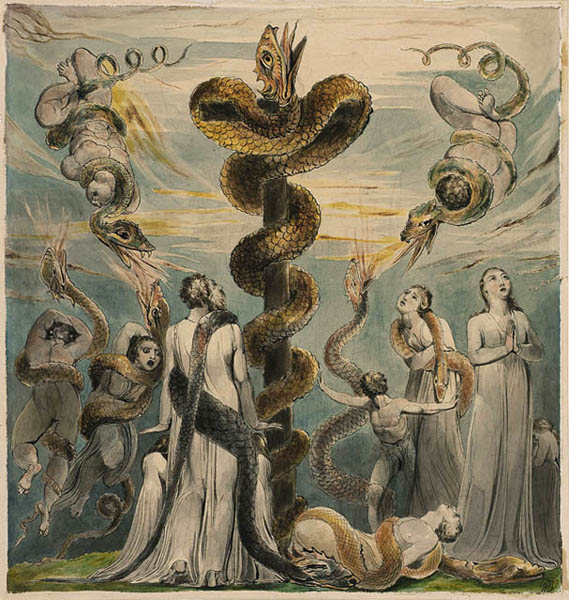

Even the serpent managed to find a place on Noah’s ark. We know because the serpent reappears in the wilderness, in the stark desert landscape that is Eden’s opposite. This time, the serpent is not an agent of sin, but the model for a divine totem charged with the power to dispel a deadly plague among the wandering Israelites. God’s most reviled creature, condemned to eat dust, somehow comes to occupy a salvific role. In the New Testament, Jesus transforms this story into gospel by way of an analogy: “and as Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, even so must the Son of man be lifted up” (King James Version, John 3:14). The serpent’s journey from the lowest of the low to the highest of the high is a peculiar development. Even more peculiar, though, for those familiar with the Old Testament, is the fact that it achieves this exalted status as a “serpent [made] of brass,” as a graven image that shines like an idol in the right light. It is a truism of biblical scholarship to say that the Old Testament is a long screed against idolatry. The commandments are explicit in this regard. So, then, what are we to make of a moment of idolatry that God does not condemn but instead actively condones? As we consider the brazen serpent, we are faced with a situation in which all the usual restrictions and taboos—against serpents and against idols—seem to be miraculously suspended.

How we understand the serpent’s presence in Eden will go a long way toward determining how we understand its representation in the wilderness. But the serpent itself is not the only link between Genesis and the Numbers story. Both stories reveal a God who seems to sanctify the act of image-making. In Genesis, God himself is the image-maker. We get not one, but two accounts of man’s creation, and in each one the language emphasizes the creativity of the act. In Genesis 1, “God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness,” words made flesh in a threefold repetition of the verb we translate as “created”: “So God created man in his own image, in the image of God created he him; male and female created he them” (Gen 1:26, 1:27). In Genesis 2 it is not through emphatic repetition but through prolonged description that we learn to see God as an artist absorbed in the physical project of “form[ing]… of the dust of the ground” the little effigy of the human body (Gen 2:7). In this double making of man we find the paradox of the image, which later in the text develops into the dangerous paradox of the idol. Man is made in the image of God and can be said to represent him—not only in form (“after our likeness”) but in function, in having “dominion” over and naming other living creatures (Gen 1:26). But in Genesis 2, we begin to sense the excesses of representation. Man might represent God, but even the transparent pleasure Yahweh takes in molding the wet red earth reveals how easily the difference of the image—here, its material difference—eclipses its indexicality. Man is named not for his likeness to God but for the difference of his form: adamah (earth), dam (blood), admoni (red).

Genesis predictably teaches us to see man as unique within Creation, but Adam’s name, which links his nature to the earth itself, encourages the question that will lead us in turn to the serpent—are we to see every element of Creation as a representation? If God is all, then what form could each thing take other than beTzellem Elohim—the image of God? Rivers, rocks, stars, flowers, creepers, crawlers: all must be shadows (tzell) of the divine mind if we are not to posit another source of inspiration. Unlike the mortal artist, the God of Genesis does not have access to a world of objects outside himself—he is always his own model. The process of creation, then, must begin with a great internal breach whereby God differentiates himself from himself: “heaven” from “earth,” “the light from the darkness,” “the waters from the waters,” “the day from the night” (Gen 1:2, 1:4, 1:6, 1:14). It is through these differentiations that God articulates a position from which he can both judge and bless. In other words, it is through a radical process of fragmentation, a sort of self-imposed Babel, that God assumes his nature and makes his name as Elohim, the one-made-many rhetorically masked as the many-made-one. “And God saw that it was good” marks the moment when, like Milton’s Eve or Lacan’s child, God catches a glimpse of his own reflection in his creation and is captivated by the beauty of his form; it is a vision of coherence ironically achieved the moment that coherence is fragmented (Gen 1:10). The serpent is the symptom and sign of this paradox.

Genesis is careful to emphasize the serpent’s divine provenance: “Now the serpent was more subtile than any beast of the field which the Lord God had made” (Gen 3:1). The Christian vision of the serpent as Satan is a rather flagrant attempt to wriggle free of the obvious problem this poses: if the serpent is indeed made by God and is itself a manifestation of God, then what are we to make of its efforts to undermine the divine plan? The serpent is an element of God’s being, which, once manifested—made and named—has taken its uniqueness to heart. It has interpreted its own form—slippery, surreptitious, self-renewing—as its nature. The serpent’s “subtlety” is its sensitivity to its separation not only from God, but also from other manifestations of God’s being. In reveling in its singularity, the serpent seems to be in line with God’s plan, or at least in the differentiating spirit of its initial gestures. We can read the serpent’s interaction with Eve as an attempt to gain a more sophisticated understanding of these differences. How, the serpent asks, am I different from the woman? Why is this tree unlike all the other trees? What is the nature of the relationship between us and our maker? Do all parts bear the same relation to the whole? In asking a related question aloud—“Yea, hath God said, Ye shall not eat of every tree in the garden?”—the serpent sensitizes Eve to the prohibitions which circumscribe her identity (Gen 3:1). By activating her capacity for discrimination, the serpent brings Eve one step closer to deviance. It is in this moment that the instability of the Edenic situation makes itself clear. Though God desires difference, he prohibits the awareness of difference, articulated as “the knowledge of good and evil,” that might lead to self-determination—and potentially, total dissociation (Gen 2:9).

But unlike the serpent, Eve does not seem to deviate from the divine order out of a desire to reify her separate identity, but rather to be, as her seducer suggests, like God. The King James translates elohim in this context as “gods,” but in either case, we read in Eve, and in Adam, a yearning for sympathy with the creator—a sympathy vociferously denied in the aftermath of their transgression. But it is not, after all, the transgression itself that so offends God, but the desire for and possibility of nearness. If the process of creation is indeed a process of differentiation, then the yearning of Adam and Eve to return to the womb-water of “the deep” is regressive (Gen 1:2). It is an effort to roll back God’s plan. Their disobedience is not the cause of their alienation from God, but its effect—evidence of the inherent rift they long to close. After God widens that rift by closing fast the gates of Eden, the descendants of Adam and Eve devise more desperate and daedalian means of approaching the being from which they came.

Much of the Pentateuch is spent reminding us that man is himself an image-maker or, more brazenly, an idolater. The golden calf is the prototypical idol—big and blatant; we might think of it as Esau to the brazen serpent’s Jacob. It is important for our consideration insofar as it comes hard on the heels of God’s most explicit prohibition against image-making. In his very first commandment as “the Lord thy God,” he links the worship of “other gods” to the human habit of making “graven image[s]” in the “likeness of any thing that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth” (Exodus 20:2-4). But the same word used to designate the “image” we wrongly worship is also the word used to establish our likeness to God when we were made in his “image.” This echo alone should serve as a warning against seeing the enthusiasm for images as evidence of man’s frivolity. The enthusiasm for images of all kinds is not the same as the enthusiasm for adornment; the incident with the golden calf makes it explicitly clear that we are eager to “brake off the golden rings which [are] in [our] ears” and melt them down for the sake of a higher project (Exodus 32:3). This project seems, almost without exception, to be originally motivated by a desire for intimacy with an abstracted or apparently absent being—or, more generally, by a desire to mend disunity. Even if we regard the household gods which Rachel smuggles out of her father’s house as fetish objects, her attachment to them indicates a fissure where Laban and Jacob have failed to make a family. The image serves as an illicit intermediary between the two worlds, just as the golden calf, which looms much larger in the Biblical narrative, is meant to serve as an intermediary between the lofty heights of Sinai and the daily grind of the desert camp.

But the story makes clear how easily the golden calf strays from its symbolic function as the seat of God to become a god in itself. Like the carved cherubim which support the divine throne, the calf is initially meant to serve as God’s mount and encourage his manifestation among the people who are not permitted to scale Sinai alongside Moses and Aaron. We are reminded, here, of image-making as an essentially compensatory act: if God will not reabsorb man into the undifferentiated being of his beginnings, then man, still longing after likeness, will try to wrestle the divine down to the level of form. This sympathetic urge, however, is not preserved. Just as the serpent comes to take pleasure in the particularity of its form allowing it to determine its nature, so too is the golden calf changed by the suggestiveness of its own form, which calls to mind much beyond what it is meant to represent. The text makes clear that the festival begun as “a feast of the Lord,” of Yahweh, ends in an eruption of sexual “play” no doubt inspired by the animal’s associations with fertility (Exodus 32:5-6). It is in this moment that the image becomes an idol—not because of the “pagan” ritual and licentiousness it inspires, but because in interpreting particular attributes of the form as constitutive of divinity and worthy of worship through mimicry, the most fundamental divine attribute of all-pervasiveness is denied. It is not that God is not present in the idol, but rather that God is not particularly present in the idol. Idolatry represents a metonymic misunderstanding in which the part is mistaken for the whole. Though the idol, as a creation within Creation, can be in no other image but God’s, this likeness does not equate to the unity man craves. The idol does not heal, but instead exacerbates, the wound of differentiation.

* * *

And yet, the idol does heal. In Numbers, we encounter the Israelites still in the desert, once again the worse for the wear in their wandering. They “spake against God, and against Moses,” asking “wherefore have ye brought us up out of Egypt to die in the wilderness?” (Num 21:5). The impulsive wrath of the desert deity is not the subject of this essay, but suffice it to say that for this loss of faith “God sent fiery serpents among the people; their bite brought death to many” (Num 21:6). What is most arresting about this story is not the rift but the resolution; “Moses prayed for the people and the Lord said unto Moses, Make thee a fiery serpent, and set it upon a pole: and it shall come to pass, that every one that is bitten, when he looketh upon it, shall live. And Moses made a serpent of brass” (Num 21:8-9). In other words, God commissions a kind of idol.

Given the violence of God’s response to the worship of the golden calf, it is natural to be wary of another graven image so soon thereafter, even if the sight of it relieves suffering.

God, after all, is a double agent here. It is God who sends serpents to torment the Israelites, and God who commands Moses to make their salvation in the image of their suffering—a symbolic reminder that both the cause and cure come from the same source. That reminder resonates not only in the wilderness but also in the garden. Here, it is possible to see the brazen serpent “set…upon a pole” as a luminous allusion to the serpent in the Tree of Knowledge—both share the same vertical geometry (Num 21:8). The serpent-in-the-tree represents our first temptation to attribute the power of a made thing to some source other than its maker. God seems to use the brazen serpent to reclaim the Edenic serpent as manifestly his creature and to resignify it as redemptive. The brazen serpent is also a clear counterpoint to the golden calf. In this case, God does not wait for his desperate people to fashion an idol of their own, and he does not risk the possibility that they might forget their idol’s connection to the divine. Instead God aggressively reestablishes the crucial links between divine forces, the wonders of creation, and the human creations made in the image of those wonders. He links the forces of life and death to the fiery serpents and the fiery serpents to the brazen serpent set upon the pole. And despite his active intervention, it is not God himself, but Moses who ultimately crafts the sympathetic sign. This detail reminds us that it is by our own hand and through our own interpretation that the serpent—form, flesh, difference, image, idol— is constituted as our Fall or our salvation.

Carina del Valle Schorske (MAPH ’13) is a poet, essayist, and editor. Her writing has appeared in the Yale Literary Magazine and Hypocrite Reader, among other venues. She is currently the guest editor for a special selection of essays on psychology and race for Transition Magazine, to be published in the fall of 2013.