Philip Lamantia’s Practical Politics

ESSAY by Joshua Kotin

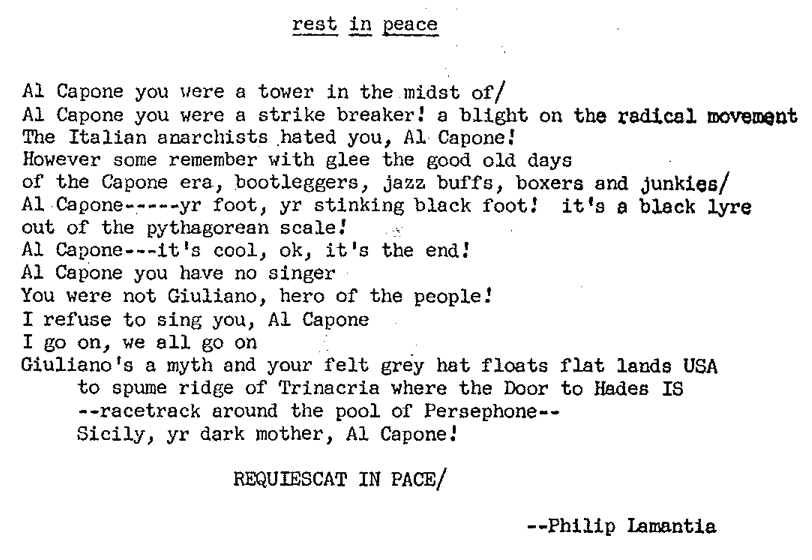

Is there a connection between the practical politics of the New Left and the ecstatic poetics of Beat poetry? Is there a way to connect poems like Philip Lamantia’s “Rest in Peace” and “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!” to a practical political program?

These were the questions that came to mind when I was asked to present a paper on Beat poetry and the New Left by the Platypus Affiliated Society in 2010. I was not interested in discussing how Beat poets paved the way for the New Left by radically reorienting cultural norms in the mid-1950s. I wanted, instead, to explore how Beat poets imagined the direct political efficacy of their work. Did Lamantia have specific political ambitions for “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!”—absurd as that may sound today?

To address these questions, I visited the archives of two literary magazines housed at the University of Chicago: Chicago Review and Big Table. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the magazines were major venues for Beat writing. They were also at the center of two important censorship controversies—controversies that foreshadowed the culture wars of the late-1960s. In this essay, a revision of my original presentation, I discuss my findings. I begin with a brief history of the two magazines and then discuss the political stakes of Lamantia’s poetry.

•

In 1958, Irving Rosenthal and Paul Carroll took over as editor and poetry editor (respectively) of Chicago Review, a literary magazine edited by students at the University of Chicago. In three consecutive issues that year, they turned a strong academic quarterly into the one of the most prominent avant-garde magazines in America. The spring issue featured new writing from San Francisco, including the first chapter of William Burroughs’s Naked Lunch, and work by Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg, among others. The summer issue, on Zen and poetry, opened with Alan Watts’s essay, “Beat Zen, Square Zen, and Zen.” The autumn issue featured more Beat writing, including the second chapter of Naked Lunch.

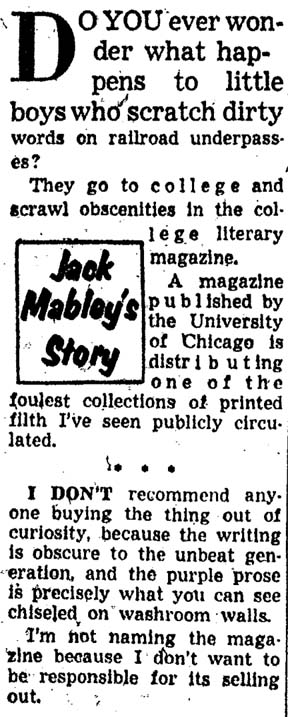

A few weeks after the autumn issue appeared, the Chicago Daily News published a front-page story with the headline, “Filthy Writing on the Midway.” The story, which focused on Naked Lunch, concluded:

A few weeks after the autumn issue appeared, the Chicago Daily News published a front-page story with the headline, “Filthy Writing on the Midway.” The story, which focused on Naked Lunch, concluded:

I don’t put the blame on the juveniles who wrote and edited this stuff because they’re immature and irresponsible. But the University of Chicago publishes the magazine. The Trustees should take a long hard look at what’s circulated under this sponsorship.[1]

Yielding to public pressure, Lawrence A. Kimpton, the University’s Chancellor, refused to allow the next issue of CR to be published. (It was to include another chapter of Burroughs’s novel.) The magazine was put under the authority of a faculty committee and told that issues now had to be “‘innocuous and non-controversial.’”[2]

In protest, Rosenthal, Carroll, and most of the CR’s staff resigned. They took the contents of the suppressed issue and formed an independent magazine, Big Table. The first issue appeared the following spring with “the complete contents of the suppressed Winter 1959 Chicago Review.” Upon publication, the magazine was quarantined by the Post Office, and the editors had to sue for its release. At the trial, the judge found in the magazine’s favor, arguing that the “dominant theme or effect” of Naked Lunch was “that of shocking contemporary society, in order perhaps to point out its flaws and weaknesses.”[3] The judge was Julius J. Hoffman—the same judge who would preside at the trial of the Chicago Eight (then Seven).

Big Table ran for five issues between 1959 and 1960, all except the first edited exclusively by Carroll. For most of the run, Ginsberg served as unofficial editor-at-large. The archives are filled with his letters recommending writers and offering ideas for special issues. He is Ezra Pound to Carroll’s Harriet Monroe—a brilliant, opinionated curator negotiating with an ambitious, yet practical editor. When Ginsberg recommends special issues on prison writing and queer writing, Carroll suggests an issue on contemporary French poetry. When he praises the young John Wieners, Carroll criticizes the poet’s “poor ear” and “inadequate technique.”[4] Ginsberg wants to revolutionize American society. Carroll wants to secure an audience. His taste is the magazine’s standard: when he rejects an idea or submission, he diligently explains that it “doesn’t get under my skin.”[5]

One of the poets most fervently promoted by Ginsberg was Philip Lamantia. Born in 1927 and raised by Sicilian immigrants in San Francisco’s Mission district, Lamantia was a poetry prodigy. His first poems were published in the surrealist magazine View when he was fifteen. Soon after, he dropped out of school and move to New York, where he spent time with André Breton, Max Ernst, and other artists, who had fled France during WWII. After the War, he returned to San Francisco, attended Berkeley, and became involved in the Beat scene. His poetry from the 1950s blends surrealism with the hallmarks of Beat writing: open forms, jazz, bohemian culture, mysticism, religion, sex, drugs—lots of drugs. He published eleven books before his death in 2005—including two volumes in 1959, Ekstasis and Narcotica, both from Auerhahn Press. The University of California Press will publish his collected poems in 2013.

After the first issue of Big Table appeared, Lamantia sent Carroll a note from San Francisco: “I had once a long letter for you before it was definitely announced, via time, inc., that your projected magazine is to be called THE BIG TABLE – wonderful title! i mean i wanted to add my suggestion, too, that it should be called that.”[6] The letter sparked a long exchange and two separate submissions, which included two poems about the current Pope: “Letter to the World Crossed by Poems for the Pope John XXIII” (which is now lost) and “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!” (which only exists in manuscript and on the linked recording).

How should we understand the political aims of “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!”? At first glance, it seems political in a wholly negative way—political in the way Judge Hoffman thought Naked Lunch was political: a form of protest, an attempt to shock society. Lamantia’s early writings support this view. In a letter published in VVV in 1944, he declared:

[A] true revolutionary poet can not help defying every appalling social and political instrument that has been the cause of death and exploitation in the capitalistic societies of the earth […] To rebel! That is the immediate object of poets![7]

From this vantage, the poem is an act of rebellion: a hilarious “fuck you” to society and its values.

But if we look at the letters in the Big Table archives, we get a different picture of Lamantia’s aims. After congratulating Carroll on title of the magazine, Lamantia describes his plans for 1959:

my objective for 1959 is to hitch a ride somehow (do you know some happy, far out ecclesiasts???) to Rome for the Council Our Swinging Pope is going to call.

I have many suggestions for We-Him-The-Pope WHO SAYS “I” instead of “we”, first of all why doesn’t Church, Holy Roman, re instate or Invent the procedure of inviting the best, swinging poets in each nation to write poems, preferably short, for the Great liturgical feasts of the year and these poems to be painted on great banners and streamers displayed everywhere inside and outside all the major churches in each bisophric???

this would really manifest the poet’s vocation in relation to the Church—as a POINTER PROPHET.[8]

Some background may be helpful: in October, 1958, Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli became Pope John XXIII. In January, he signaled that he would call an ecumenical council, which became the Second Vatican Council (1962–1965). The council, which Pope John did not live to see complete, revolutionized the face of the Church, by, among other things, allowing liturgy in vernaculars and promoting dialogue with non-Catholics. This is the council Lamantia means.

It may come as a surprise to learn that Paul Carroll took this objective to go to Rome at face value. He invited Lamantia to contribute an essay on his hopes for the Church: “I got to wondering if you might not want to expand yr ideas & hopes about the Church into some kind of prose essay (it can be short): I don’t know anyone else I would rather read on the Church than you.”[9] “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!” was Lamantia’s second response to the invitation, after Carroll rejected “Letter to the World Crossed by Poems for the Pope John XXIII.” Writing from Mexico, Lamantia proclaimed that “My piece conveys a REAL ATTACK, gospel-restatement, on jansenistic, puritan – without sensational porno come-on – and yet WILD PRAISE OF MYSTICAL ELEMENT IN CHURCH AND UNCOMMON MONARCHIC SALUTE TO THE PRESENT POPE.”[10]

This context should not, I think, cause us to read the poem as sincere (whatever that might mean) or to take Lamantia’s “objective for 1959” at face value. But we should note that Paul Carroll took the poem and objective seriously—that a sober, practical reader thought that Lamantia had something to contribute to the Church and that the Church might listen. The Lamantia-Carroll correspondence, in this way, tells us a lot about the age and its sense of the potential efficacy of poetry. There is real confidence that one of the most powerful institutions in the world might be open to advice—and advice from the author of Narcotica no less. Lamantia’s ecstatic poetics is, at this specific moment, also a practical politics.

In the 1950s and 60s, many writers associated with the New Left saw the Church (and Christianity, more generally) as an antidote to technocracy, to an increasingly administered world, to a world headed for nuclear war. This is not only the perspective of religious writers like William Everson (Brother Antoninus) or Thomas Merton. The sociologist C. Wright Mills presented just such an argument in his essay “A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy” from 1958—

It is as if the ear had become a sensitive soundtrack, the eye a precision camera, experience an exactly-timed collaboration between microphone and lens. And in this expanded world of mechanically vivified communications, the capacity for experience is alienated, and the individual becomes the spectator of everything but the human witness of nothing.[11]

This is from a discussion of why Christians should act according to conscience and dogma, and resist the nascent military-industrial complex. Lamantia’s “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!” is part of this discussion—an attempt to influence Church policy, but also to transform alienated spectators into human witnesses.

In the end, Carroll decided not to publish either poem about Pope John XXIII. Here is his rejection of “Letter to the World Crossed by Poems for the Pope John XXIII” (his rejection of “All Hail Pope John the Twenty Third!” is not in the archive)—

The final decision, I am afraid, went against printing “Letter to the world crossed with poems for Pope John 23.” To say I am sorry about this would be puerile in the face of the passion & inspiration I feel went into the writing of that Letter. I must say, in honesty, that tho I was moved by the Letter, it didn’t get under my skin, which is the only test I can trust in the end. What I am trying to say is: the energy & passion which breath from the Letter are somehow mitigated, it seems, but the lack of precision in the style…[12]

Lamantia’s response was sharp:

What’s going on? Do you want “Masterpieces”, vide Artaud on “No more masterpieces”… or do you want just the sensational stuff to get the cops down on you? me thinks you want to make a thing out of the beat, but man, that’s dead DEAD DEAD ALREADY! all i can figure is No more dullbeat and Whitman-Rimbaud constipational… there IS something else!

I dunno, I’m not necessarily writing to “get under” yr or anybody else’s “skin”. other levels![13]

Carroll, in the exchange, prioritizes the values that Lamantia is trying to transcend: the personal, the private, the precise, the merely provocative. Ultimately, the efficacy of the poem proves illusory. What does this fact tell us about the specific political ambitions of Beat poetry? Not much. It simply reminds us that established institutions are resistant to change.

The fifth and final issue of Big Table included an announcement for a planned sixth issue on “Post-Christian Man,” which would have featured work by Allen Tate, Russell Kirk, Paul Goodman, and William Phillips—exactly the kind of issue that made Chicago Review into an important academic quarterly in the first place. Perhaps recognition of this fact is what caused Carroll to cease publication of Big Table.

•

Joshua Kotin is assistant professor in the Department of English at Princeton University. From 2005 to 2008, he was the editor of Chicago Review. From 2009 to 2011, he was a preceptor in MAPH.

This essay is dedicated to Eirik Steinhoff. I thank Garrett Caples, Steven Fama, and Nancy Peters for answering questions about Lamantia. I also thank the estate of Philip Lamantia for permission to quote from his letters.

[1] Jack Mabley, Chicago Daily News, 25 October 1958: 1.

[2] Irving Rosenthal quoted in Albert N. Podell, “Censorship on the Campus: The Case of the Chicago Review,” San Francisco Review 1:2 (Spring 1959), 80. For a full and more nuanced account of the controversy, see Podell, 71–87, and, especially, Eirik Steinhoff, “The Making of Chicago Review: The Meteoric Years,” Chicago Review 52:2–4 (Autumn 2006): 292–312.

[3] Big Table, Inc. v. Schroeder, 186 F. Supp. 254 (N.D. Ill. 1960).

[4] Paul Carroll to Allen Ginsberg, 20 September 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 44, University of Chicago Library.

[5] See, for example, Paul Carroll to Philip Lamantia, 23 May 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[6] Philip Lamantia to Paul Carroll, 10 February 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[7] Philip Lamantia, “Surrealism in 1943,” VVV 4 (February 1944): 18.

[8] Philip Lamantia to Paul Carroll, 10 February, 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[9] Paul Carroll to Philip Lamantia, 7 March 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[10] Philip Lamantia to Paul Carroll, 29 May, 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[11] C. Wright Mills, “A Pagan Sermon to the Christian Clergy,” in The Politics of Truth: Selected Writings of C. Wright Mills, edited by John H. Summers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 165.

[12] Paul Carroll to Philip Lamantia, 23 May 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.

[13] Philip Lamantia to Paul Carroll, 29 May, 1959. Paul D. Carroll Papers, box 1, folder 62, University of Chicago Library.